THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL CELEBRITY CHEF: THE GENIUS OF ANTONIN CARÊME

When it wasn’t the almost equally great Alexis Soyer.

Excerpted from Ian Kelley’ article “Crème du Carême” in The Guardian Sunday, 12th October 2003.

1783: Left Bank slums of Paris, Antonin Carême was born.

When nine years later Paris stood out for horrors and turmoil, Antonin's father took young Carême to the busy Maine gate and abandoned him with these words: “Nowadays you need only the spirit to make your fortune. Va petit! (‘Go little one’) with what God has given you.”

Antonin was taken in by a busy cook who offered him bed and board in exchange for menial tasks.

It was the start of his career.

1829: Early evening 6 July, Paris,

Lady Morgan, reflecting upon her dinner invitation, travelled in a hired barouche on Les Champs-Élysées. She had been told. 'You are going to dine at the first table in France - in Europe - to taste for yourself, the genius!'

“An invitation from the Rothschilds had incited both jealousy and awe at Lady Morgan's Paris lodgings, and not just because James and Betty de Rothschild were the richest couple in France. Their chef, known to everyone, was Antonin Carême. And all of Paris wanted to eat à la Carême.”

Apple Charlotte, Turbot À la Hollandaise, Salmon À la Rothschild. Carême's recipes were on everybody's lips.

So, for the first time a chef became a celebrity.

12 hours earlier:

A slight, ashen-faced man, looking older than his 45 years, breathed with difficulty in the early-morning Paris fug. He was slowly dying from the poisonous fumes of a lifetime of cooking over charcoal. He was on his way to the Rothschilds' château in Boulogne-sur-Seine.

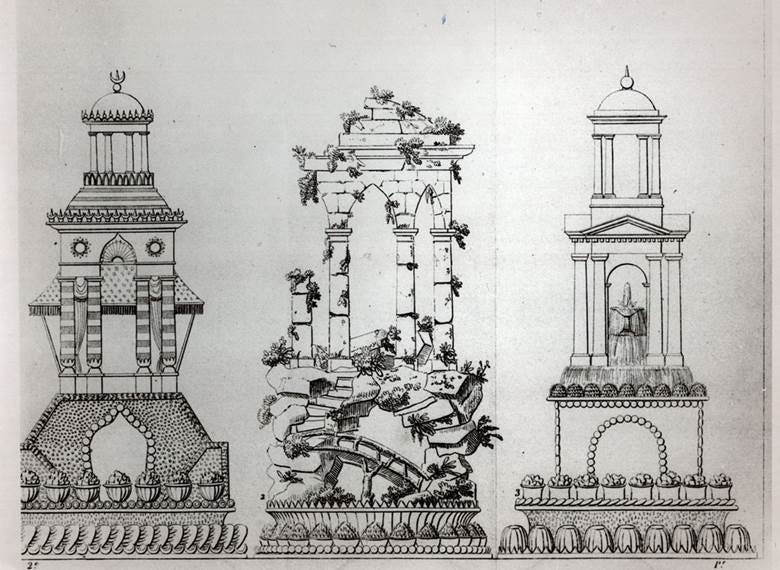

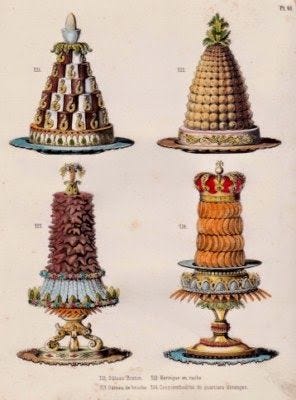

“For a man who had once fed 10,000 on the Champs-Elysée, this was small potatoes. Even so, work had begun the day before. Crayfish and brill, eel, cod and sea-bass, quails, chickens, rabbits, pigeons, beef and lamb had been ordered from Paris markets, along with specified offal of calves' udders, cock's-combs and testicles. As well as the best Mocha coffee and truffles. Isinglass (fish gelatin) and veal stocks had been prepared, cream supplied locally, and the château’s ice-house restocked. The vegetables and fruit for the menu would come from the Rothschild gardens. Antonin had also already begun work, with his young assistant, Monsieur Jay, on the sugar-paste foundations of a table-length 'extraordinaire' in the form of a Grecian temple, the Sultane à la Colonne.”

Grosses Pieces

That day 7am:

“A hush descended on the château kitchens as Carême arrived.

The scullery maids and female staff curtsied and then departed. Antonin took off the diamond ring from the index finger of his right hand, a gift from a grateful Tsar, and rolled up his sleeves. He put on a white toque, a fashion he had created himself.

The evening menu consisted of seven services offering 18 choices of dish to the dozen guests. For his French employers it was to be “service à la francaise,” where nearly all the food was presented on the table at the start of the meal, with only the soups and entrées literally 'making an entrance' hot. Service à la russe, or plated courses in sequence, was a fashion too daring for the socially ambitious Rothschilds. They were paying 8,000 francs per annum (£125,000 in today's money) for Antonin's occasional services to get what they wanted.

The roasts and highly dressed “grosses pieces” would adorn the table as the guests arrived, along with the side-dishes including the center-piece dessert, the Sultane, which would remain on the table all evening. The kitchen day began with dessert. Antonin selected fruits for the puddings - a nectarine ice cream and oranges stuffed with layered jellies.

It was a hot, close day, and he ordered that the windows of the dining-room be kept shut, but for the internal fountains to play; the best that could be done in terms of air-conditioning.”

8am

“Back in the kitchens the stoves were already stoked and the stoves filling up with pans of stocks. In the cooler confectionery room Jay hollowed out oranges. Antonin arranged the two dozen oranges in a fruit colander filled with crushed ice. The cooling isinglass was brought from the kitchen along with blood-red cochineal, clarified syrup and the nectarine marmalade. Antonin poured the thickening isinglass alternately into the fruit juice and the almond milk. He added strained cochineal, drop by drop, and lemon juice to the orange jelly, and poured the creamy blancmange or viscous amber juice into alternate orange shells.

Throughout the day he would return, adding more.”

11am

In the kitchen “Quails lay in ordered ranks, headless and tied. There were baby rabbits and pigeons, partridges and chickens were being chopped, washed, disemboweled and stuffed. The cock's combs and testicles were set aside for the vol-au-vents. Bones and feet were reduced to thicken glazing-stocks.

Seven hours until dinner. Antonin called for more charcoal, and champagne.

Midday

For the sugar temple table center piece, they prepared sugar syrup. As the sugar began to boil, Antonin reached for calcinated alum and then cream of tartar to add, a pinch at a time, into the sugar lava.

“Freezing his hand first in iced water, Antonin then plunged it straight into the boiling sugar, and back into the cold. A kitchen-boy gasped. Carême's pastry chef trick never failed to impress. He repeated the process, then took a knife, dipped it into the top of the sugar and then into the cup of water. He brought it straight out, cracking the crystalline sugar clean from the knife. The sugar was cracked and ready to spin. Antonin stood back from the stove with the first spouted pan. He held the base mold at his waist and raised the pan to head height and started to pour. The thread of sugar fell towards the mold, like a perfect skein of hot wax, and Antonin laced it round in one continuous movement.”

Next, he spun sugar for the columns, rolling bundles of them together, seven inches high, and fashioned plinths, column tops, and pedestals. “Later, Antonin would garnish his Sultane à la Colonne with meringues, choux glazed with caramel, chopped pistachios and small white pastries. He would add some fallen columns in the Romantic style, a little 'moss', made from almond paste dyed green with spinach, and, on the column, which would be nearest the most honored guest, write in royal icing her name: 'Lady Morgan'.”

4pm

The heat was intensifying in the kitchen. Antonin prepared the roasts on spits and the cauldrons for boiling meat and fish. He called for ice to keep the desserts cold in the confectionery room and the pastry room cool enough for the unbaked pastries.

6pm

In the dining room “two staff brought the Sultane à la Colonne to the dining pavilion.

“A footman, feet bound in protective padding, stood on the table to guide it into position, the column dedicated to Lady Morgan and facing her place.”

6:30 pm:

Carême described the scene in the kitchens.

“One sees 20 chefs in the cauldron of heat. “Look at the great mass of burning charcoal... for the cooking of entrées, for the cooking of the soups, the sauces, the ragouts, the frying and the bains-maries. Add to that a heap of burning wood in front of which four spits are turning, one of which bears a sirloin weighing forty-five to sixty pounds, another a piece of veal weighing thirty-five to forty-five pounds, the other two for fowl and game. In this furnace everyone moved with tremendous speed, not a sound was heard, only I had the right to be heard and at the sound of my soft voice, everyone obeys. Finally, to put the lid on our sufferings, for about an hour the doors and windows are closed so that the air does not cool the food as it is being dished up.

And in this way, I passed the best days of my life.'”

7pm:

Lady Morgan took her place next to James de Rothschild. Amid the hubbub of German, Italian, English and French, the footmen entered and, as the soups were served, silence fell. “In the kitchens, there was no such calm. Although the roasts and the grosses pieces were already on the table, the meal proper was now about to begin. The fish were sent out with heated plates and a new set of cutleries: a knife and three-pronged fork to replace the soup spoons.”

And soon it went, ending with my favorite custard sauce:

Crème du Carême

Crème anglaise with the addition of Maraschino. Nothing to do with red cherries for cocktails, but the clear liqueur made with the slightly sour fruit of the Marasca cherry tree (Prunus cerasus var. marasca). And very preferably made by Luxardo.

Sublime and way more than the sum of its parts.

Lady Morgan (1781? – 1859)

A, travel writer, radical, romantic, and "proto-feminist" with political and patriotic overtones. She counted Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron among her defenders.

Carême

Thank you, Chris, and as for the style, cannot help but dream while writing!

Will find it. The trailer is total fantasy, but pretty.