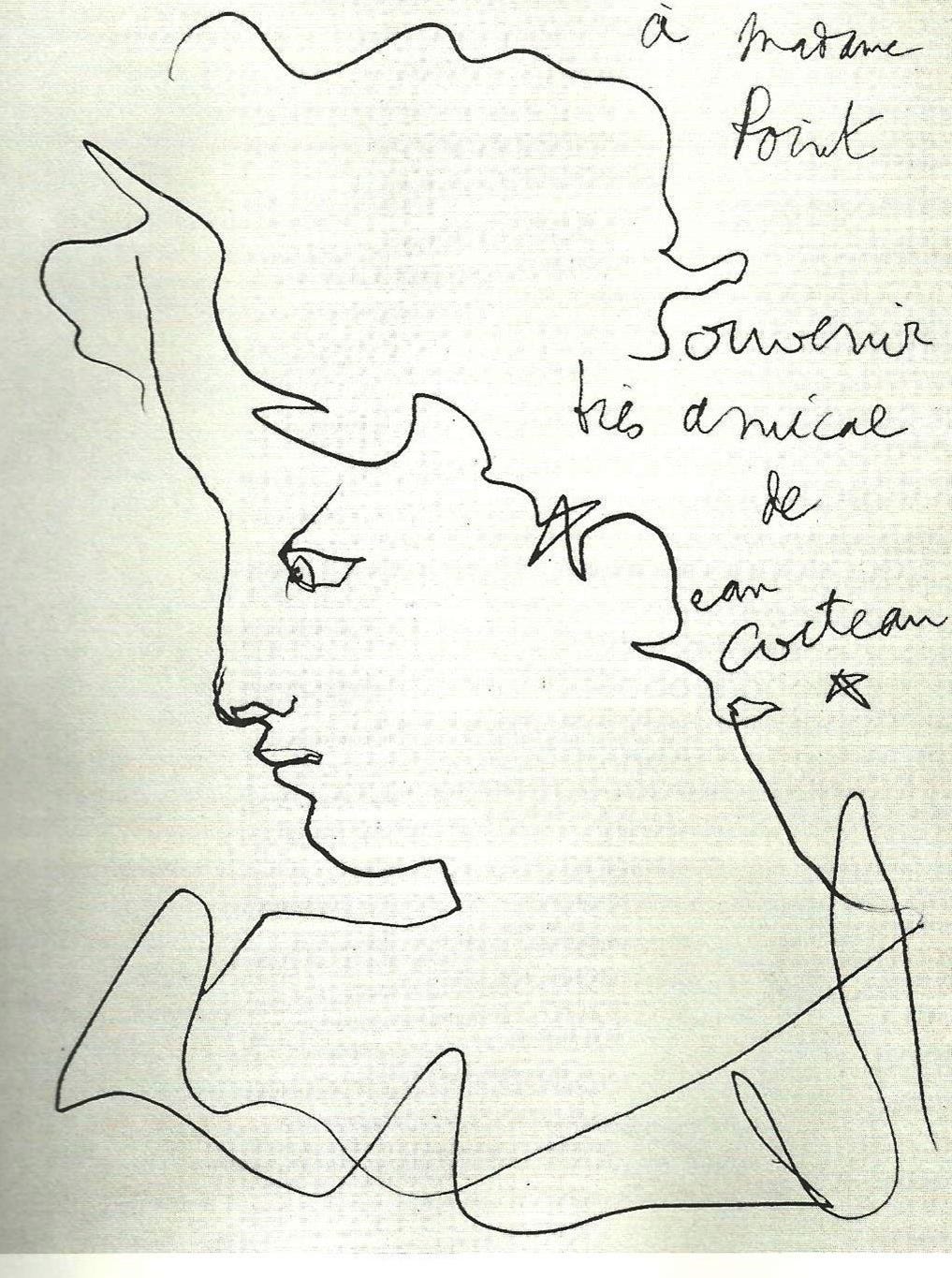

After lunch in 1955 just months after the death of the great Fernand Point at his legendary restaurant La Pyramide, the already legendary poet and filmmaker and frequent guest at the restaurant, Jean Cocteau, asked the new widow Marie-Louise if the Le Livre d’Or or visitor’s Golden Book was still in play.

She told him that she had locked it up the day her husband died.

“But for you, Monsieur Cocteau, I will make an exception just this once.”

The book’s first entry was in 1931 with the Aga Khan’s “What an excellent luncheon.” Then, over the subsequent years, it was filled with the raves of gourmande and author Colette, various presidents of France, stage actor, film actor, director, screenwriter, and playwright Sacha Guitry, the Nobel Prize winning playwright and composer of Pelléas and Mélisande Maurice Maeternlink, some of the richest Rockefellers, a glowing Vivien Leigh with hubby Laurence Olivier without any of his boyfriends, the emperor of D-Day general Eisenhower, Josephine Baker without her loin cloth of gold feathers, Dietrich in trousers with Gary Cooper, Clark Gable wearing Sulka velvet slippers, chanteuse of love gone wrong Piaf, the now very rich Picasso, and many, many more.

Madame Point took the book and opened it to the last time Jean had signed the book for her.

This 1955 afternoon the great writer took out his Cartier pen and went to what was to be the final page. Not accepting that such a great presence as Point could disappear, he wrote:

“I close my eyes and once more see the garden, the sun, Fernand being shaved, you knotting his tie. And you and the staff with eyes full of love. With Fernand, it is the true extravagance that perishes: the extravagance of the heart. But thank God, you are there.

I embrace you.

Jean Cocteau.”

On the ride back to Paris Cocteau explained what he had meant by extravagance.

“I mean the kind that is intuitive.”

As when Fernand refused to collect the newly minted meat coupons in the early months of the war from those fleeing the oncoming Nazi invaders. Or when the evening service became more and more dominated by Nazi general staff and Occupation government ministers, Point closed La Pyramided for dinner and opened only for lunch. When the occupiers started demanding tables during the day, he closed the restaurant altogether.

For six months, reopening only upon Liberation. Such extravagance lead to a Legion of Honor and a Distinguished Service Medal from King George VI of England.

And then Cocteau and Madame reminisced about the very stay-at-home Point took his food on the road.

In May 1937 he cooked Sacha Guitry’s birthday dinner for 100 guests at Guitry’s house in Paris. From his entire kitchen brigade came forth:

Fish soup

Truffled Bresse Chickens (cooked in a pigs’ bladders and served only with the truffles and the natural chicken juices)

Terrine of Foie Gras

Salade Pyramide

Favorite Cheeses (Saint-Marcellin)

Profiteroles and a Marjolaine of Fruits.

Finally, the moment arrived to settle the enormous bill for the feast that included oceans of champagne, Chateau Cheval-Blanc and Chateau Chalon. Point refused to accept any payment. “Here, I am not in my home,” he said, “so please allow me to consider myself your guest.”

Beautiful extravagance.

At home, chez Point, more extravagance was Point experimenting with his famed gratin de queues d’ecrevisses (gratin of crayfish tails) for nearly seven years before he and Madame P. agreed that it had been perfected and could be offered to their guests. As they did with the equally famed cake, the Gateau Marjolaine.

Intuitive because, as Point told his cooks, the most difficult dishes to make generally appear to be the simplest. “After all,” he said, “success is the sum of a lot of small things correctly done.”

The famous chef Charlie Trotter described Point's Ma Gastronomie as the most important cookbook.

And another famous chef, Thomas Keller: “If someone were to take away all my cookbooks except for one, I would keep Fernand Point’s Ma Gastronomie. For me, his philosophy instilled what cuisine is all about: generosity and hugeness of heart. Point said that if you are not a generous person you cannot be in this field. I think you’ll notice that chefs, as a whole, say yes to any project, fundraiser, or tasting because they have such a generous spirit.”

From the eggyguru.com: Chef Point believed in using the best ingredients possible. Regional ingredients, in season, quality-grown. His culinary philosophy was simple: The easiest dishes are often the most difficult. An often-told story is how he would always invite visiting chefs to show off their skill by cooking a simple fried egg. They would, inevitably, fry the egg too fast, in too hot a pan.”

And my comment: which is why all photos of fried eggs these days have curled brown edges. You just know they are leather.

“He would insult them and show them his way. His way was slow, careful cooking with plenty of butter.

Chef Point’s Fried Egg

Place a lump of fresh butter in a pan, and let it melt just enough for it to spread and never until it is browned. Open a very fresh egg onto a small plate or saucer, and slide it carefully into the pan. Cook on heat so low that the white barely turns creamy and the yolk becomes hot but remains liquid. In a separate saucepan, melt another lump of fresh butter, remove the egg onto a lightly heated serving plate; salt and pepper it; and then very gently pour the fresh, warm butter over it.”

A cover on the pan for a couple of minutes also helps.

Thank you for reading Out of the Oven. If you upgrade for the whole experience, and pay $5 a month or $50 a year, you will receive at least weekly publications, as well as menus, recipes, videos of me cooking, and full access to archives.

Well, at Bocuse, you were almost Chez Point. B was the urchin who poured P's champagne in the morning. Also drinking.

Yes, and what better way than this write a metaphor?