The closer we get to the US elections, the more I think of the Titanic.

And of all the ships (“liners” as transportation not cruising) I have been on that didn’t hit something which sank it.

I was eight years old and about the SS Australia, sailing between Australia and Italy, my first ocean voyage. Up to that point had traveled only on trains across America and on Pan American planes, including a DC 3 across the Pacific Ocean. But my father’s stories of his trip on the RMS Mauretania with the President of the United States, had me enthralled.

Before I knew about sea sickness.

RMS Mauretania, Atlantic Ocean, 1929

Eight days after American newspaper headlines screamed “Billions Lost as Stocks Crash,” my father was sitting at dinner on the world’s largest and fastest ship with President Elect Herbert Hoover. Exactly thirteen years to the day before I was born. Not too many years after that I was gorging myself at three meals a day on my own trips aboard transatlantic Cunard liners.

Looking at this menu now, with my father’s flourishing vertical signature of W. S. Tower, and imagining what I would have ordered as a teenager tucking in on my birthday.

I know I would have sped through the dishes in anticipation of the “Pouding Glace Nesselrode.” I would not yet have read Francatelli’s The Royal Confectioner (1846) or heard the story that this fabulous dessert was first served to Count Karl von Nesselrode by the greatest chef in the western world at the time, Antonin Carême.

Photo Courtesy of Sacher.com

Fabulous because it is a frozen mixture of marrons glacés or candied fresh chestnuts (one of my favorite things in the world), Maraschino-flavored custard or crème anglaise, and raisins and currants cooked in syrup. Unmolded, perhaps in the shape of a beehive, and served with a sauce of more very cold Maraschino custard. According to that other very great cookbook author Jules Gouffé in his The Royal Pastry and Confectionery Book (London, 1874).

I love the idea of saucing ice cream with its custard base.

On top of all that delicious richness is almost my favorite dessert sauce (vying with any kind of hot or cold sabayon or zabaglione), the haunting Maraschino-flavored custard sauce as invented by the great French chef August Escoffier.

Since Carême was his mentor, he called the sauce “Crème Carême.”

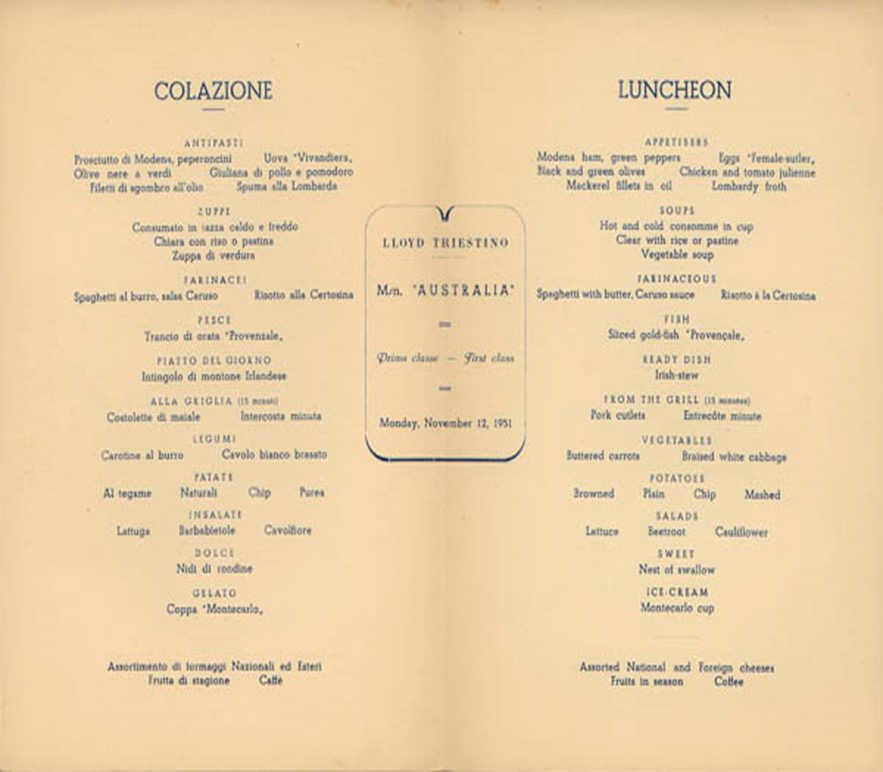

M/v Australia

That DC 3 had proved that motion and I were not ideally partnered.

My first ship proved that beyond any possible doubt.

Two days out of Sydney we were hit by a tornado in the Great Australian Bight, one of the most vicious and notorious bodies of water in the world.

No one had told me.

I was retired to bed immediately after the first great wave poured over the bridge and stunned, maimed, or tore asunder the guts of most of the officers up there, including the captain. On news of this, and the fact that the ship would not stop almost simultaneously pitching and rolling, turning the vessel into a corkscrewing mess of steel, my father though all of us had better be strapped in. At every pitch the propellers would rear out of the ocean, clearing the water completely (so I was later told) and do their best to reverse the direction of the already rotating ship, shaking it to pieces.

All this I felt through a haze of consciousness from which I was rudely slapped back to life by the occasional worried visits of our cabin stewardess, Maria, who would sweep in with huge trays of steaming, garlic-reeking, food, saying: “You must eat, you must eat. Mangia! Mangia! Weakly I would beg here to take away the eggs shirred in green olive oil and anchovies. And the rich fish stews. And the pork covered in fried onions.

I vowed to myself to kill her just as soon as I could move.

We did make it to Rome, which was not moving, so I fell in love with its cooking.

From there we took a United State liner to New York.

SS Independence

The ship’s food was pablum by comparison.

Waffles and maple syrup, ham with pineapple, chicken salad with peaches - all of it a peon to WASP country club living. I could not eat any of it, never having tasted that kind of food, but did discover the pleasures of trout, American beef, and Baked Alaska. My brother ate himself unconscious, when he was not falling after an heiress of the Firestone family. My sister ate nothing, pining away for the company of Will Durant and his wife, and my mother took a well-earned rest away from all of us: she had hired a nanny in Italy.

The next ship was from Australia to England. New York to Southampton, 1952.

RMS Elizabeth

The Elizabeth was at the height of her glory when we sailed on her that year from New York to Southampton, a few weeks after my ninth birthday. She was the perfect culmination of our trip that started in Sydney and was planned to end in London. We had moved, again.

Orange juice, strawberries in cream, kippers with eggs en cocotte (paired together raised a few eyebrows), and a side of sausage was my choice.

Not my first ocean voyage, but she was the first with the grand elegance and style.

People dressing correctly for dinner was, of course, marvelous, but the menu and the attention I received from the staff, as I dined alone at the early seating, was what held me the most.

Having taken the cruel edge off my hunger in the afternoon with neat and very precise chicken and watercress sandwiches, as only the English in all their fanaticism for afternoon tea, can make, served in superbly heavy damask linen and brought to me at my deck chair where I had been tucked in by a solicitous steward. I was, nevertheless, anxious each evening to get down to the serious business of dinner. I had soon made my preferences known, and the smoked salmon would appear at my appearance at the table (as a special order because I knew they had it) as, each evening, I would watch intently the managed art of slicing the salmon thinly so that, like great hams, its flavor can be most appreciated.

I did not know yet about Artichokes Barigoule or learned to love Calves’ Head Vinaigrette, but before the voyage had ended, I was accustomed to salmon three times a day, building a passion for it which had never subsided, if the supply often has.

But at first it was less of a passion as inspiration for serious thinking about the menu through which I would skip, lighting here, dabbling there, building a crescendo, culminating invariably, or alternatively, in Crepes Suzette or English trifle – the proper kind, with fruit freshly crushed, preserves finely made, the custard like velvet, and the syllabub cream a masterpiece of partnership between very obliging Cornish or Devon cows, a pastry chef’s boy apprentice, and the left-overs from the sommelier’s decanters of sherry and Madeira.

Then at the close of that first meal I would try not to linger, so that there would be a noticeable period between my finishing and my appearance at the next seating; the one that my parents attended, a very adult affair. The second dining would be no gourmandise, merely a souper. More salmon, naturally, perhaps an oyster or two off my mother’s plate, something from the cold buffet, and cheese with fruit.

The cheese was an excuse to dip as heavily as possible into my parent’s wine – from their bottle or, if they were dining with the captain, from a house decanter courtesy of the sommelier if I was dining alone at their regular table. The wine was the real reason for my second wind.

It came of no surprise to anyone that one night I could not get out of bed from a nap after lunch to go to dinner. I thought it was the onslaught of mal de mer. My parents knew it was my liver in full protest.

Miserable for missing dinner, but physically quite happy to do so as I lay in bed wondering if it was sage to even think, let alone dream, of the food that I was missing, there was a knock at my stateroom door. To my bid for whoever was at the door to open the door it did, and first appeared a large dining room trolley covered in miles of white damask, and then the face of our dining room waiter.

I am not sure what shocked me the most – the whole event or the presence of a dining room staff when it should have been the stateroom steward.

He then appeared, laughingly, from behind and with a flourish lifted off the huge silver dome that covered whatever was on the trolley. Revealed was a single, solitary, child-sized, green, and very plain earthenware casserole with a lid. My eyebrows once raised in astonishment at the giant silver dome then lowered in disappointment at this diminutive, little pot. When I heard it came directly from the chef, worried about his littlest and chiefest fan, my eyes then widened enough to peer under the barely raised lid.

All thoughts of mal stomach disappeared with the first whiffs of a Lancashire Hot Pot, and one of the most delicious meals I had ever tasted: plain, ordinary, a ‘simple’ stew of lamb, water, herbs, and potatoes. The next day I was up and about, none the wiser, but feeling a great deal better.

A little wiser, perhaps, for I shall never forget the glory in the simplest of fares.

Nesselrode Pudding or Crème à la Nesselrode

Photo Courtesy of https://frodenheng.lu

“Count Nesselrode was a 19th-century Russian diplomat who lived and dined quite lavishly. As a result, he had a number of rich dishes dedicated to him by chefs. The most famous is Nesselrode pudding, developed by his head chef Mouy. It consists of cream-enriched custard mixed with chestnut puree, candied fruits, currants, raisins and maraschino liqueur.”

Photo Courtesy of Prlib.com

It is important to get the best maraschino liqueur (nothing to do with those red cherries), and the best I know is from Luxardo.

The recipe adapted from https://www.jamesbeard.org.

1/2 cup (90 gr) currants

1/2 cup (90 gr) raisins

Cognac

5 egg yolks

3/4 cup plus 3 tablespoons (160 gr) sugar

3 cups (710 ml) heavy cream

One 15 oz. (450 gr) can unsweetened chestnut purée

½ cup (90 gr) candied chestnuts, broken into small pieces

2 (10 ml) teaspoons vanilla

Soak currants and raisins in Cognac barely to cover for 1/2 hour. Drain, reserving the Cognac. Beat egg yolks either in a mixer or with a whisk for about a minute, then add 3/4 cup sugar and continue beating until the mixture is very thick, a light lemon color, and forms a ribbon.

Proceeding as if you are making a crème anglaise:

Heat 2 cups of the cream in a saucepan just to the boiling point, when small bubbles appear around the sides. Don’t let it come to a full boil. Beat the cream into the egg yolk mixture and return it to the pan. Cook over medium heat, stirring, until it coats a spoon thickly. Don’t let this mixture boil. Remove from heat.

Add Stir in chestnut purée and the candied chestnuts. Add the reserved Cognac, currants, raisins, and vanilla.

Whip the remaining cup of heavy cream until it begins to thicken, then add 3 tablespoons sugar, and continue beating until it is quite firm. Fold this into the chestnut mixture, making sure they are well combined and thoroughly blended.

Lightly oil a 1 1/2–quart melon or charlotte mold and fill with the mixture. Cover securely.

Leave the mold in the freezer for about 5 to 6 hours, or until frozen solid.

To serve, unmold it onto a chilled serving dish—you may have to run a towel, wrung out in very hot water, over the mold to loosen the pudding or dip the bottom of the mold in hot water for just a second, not long enough to melt it.

Garnish the frozen pudding with whipped cream.

Chestnut Soufflé Pudding

Or here is one from the master chef Escoffier.

“Cook two lbs. of peeled chestnuts in a light, vanilla-flavored syrup.

Rub them through a sieve, add five oz. of powdered sugar and

three oz. of butter to the puree and dry it over a fierce fire.

Thicken it [when cool] with eight egg-yolks and finish it with the whites of six eggs, beaten to a stiff froth.

Poach in buttered molds in a bain-marie.

As an accompaniment, serve, either an English custard, or a vanilla-flavored apricot syrup.”

Thank you for reading Out of the Oven. If you upgrade for the whole experience, and pay $5 a month or $50 a year, you will receive at least weekly publications, as well as menus, recipes, videos of me cooking, and full access to archives.

Well, Daniel, if you arrange it and are on board as well, let's do it!

With all the reality TV out there, how is it that nobody's scooped you up and put you front and center, with the gifts of your imagination and talent for weaving stories together?

AI, if you're listening, point some directors toward Jeremiah Tower's direction.