Now that the James Beard Foundation Awards are upon us, and I found 2 days ago a copy of his completely captivating reminiscences, Delights & Prejudices. A celebration of perfect ingredients and how they are the force behind any inspired menus and cooking. It is my favorite of his books and perhaps the only one he actually wrote.

It’s time to celebrated Jim again.

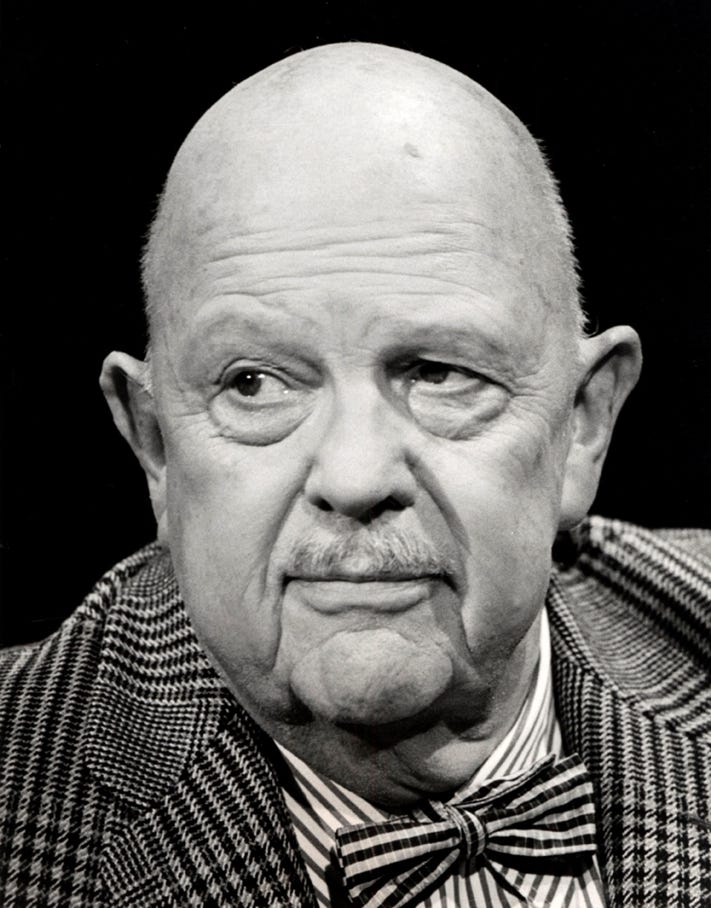

He was hailed as “The Father of American Gastronomy.”

As far away as Australia, the great food writer for The Sydney Morning Herald, Leo Schofield, said that James Beard was the person who “liberated American cooking from Gallic shackles. Beard’s name remains synonymous with American food and the foundation named after him as a center for showcasing emerging chefs in the United States. It is still going strong with its national annual awards held every year. And don’t miss re-reading Delights & Prejudices, (1964), one of the most delightful culinary memoirs ever.”

Jim was not as large as his hero, the mountainous Fernand Point, but his bald head, height well over six feet, baby blue linen suit and pink scarf, and gold wire filigree bracelet around his huge wrist fluttering over a bowl of pot-au-feu as he exclaimed in booming voice, “EXQUISITE!” all made him stand out in a crowd.

He was instantly recognizable, and he liked that.

Bottom of Form

By the time he died in 1985 he was the most famously respected culinary figure in the United States. So respected that he was intimidating for most of his fans, especially when they didn’t behave as he thought they should.

Beard had two parts.

The big jolly one, and the big tempered one.

Until I had seen the temper-induced flapping and flying of his weighty and ponderous jowls, their quivering a preface to an even more serious seismic body event and stentorian roar, I realized I had known only the jolly man. I had taken him to lunch at his choice of a San Francisco Nob Hill eatery, where we were oiled to the table by the maître d. The owner’s prostration made Jim nervous from the outset. Nothing went well. The food was mediocre, our guests fidgety. Jim’s already pink face turned even redder, splotched with streaks of purple by the time dessert was finished. When his espresso arrived, his jowls went into full swing.

“WHO asked for lemon zest IN the coffee,” he roared.

The waiter looked as if he might make a puddle. Soon Jim’s cane was found and he launched himself, Robert Morley-like, into the foyer.

“And furthermore, the coleslaw was TERRIBLE!”

To defuse the moment, I said: “OK, Jim, whose coleslaw is better? Your uncle Billy’s or my aunt’s?” Both were in our respective cookbooks. Jim looked at me fiercely. His body stopped heaving and began to roll. Tears appeared and he roared again, this time in laughter.

Apart from his thirty or so books published over thirty years, perhaps his greatest accomplishment was to create in 1959 with Restaurant Associates and “The Four Seasons,” arguably the most important grand restaurant in the United States since the great and ground-breaking Delmonico’s defined American cooking for the 19th century and the first twenty years of the 20th.

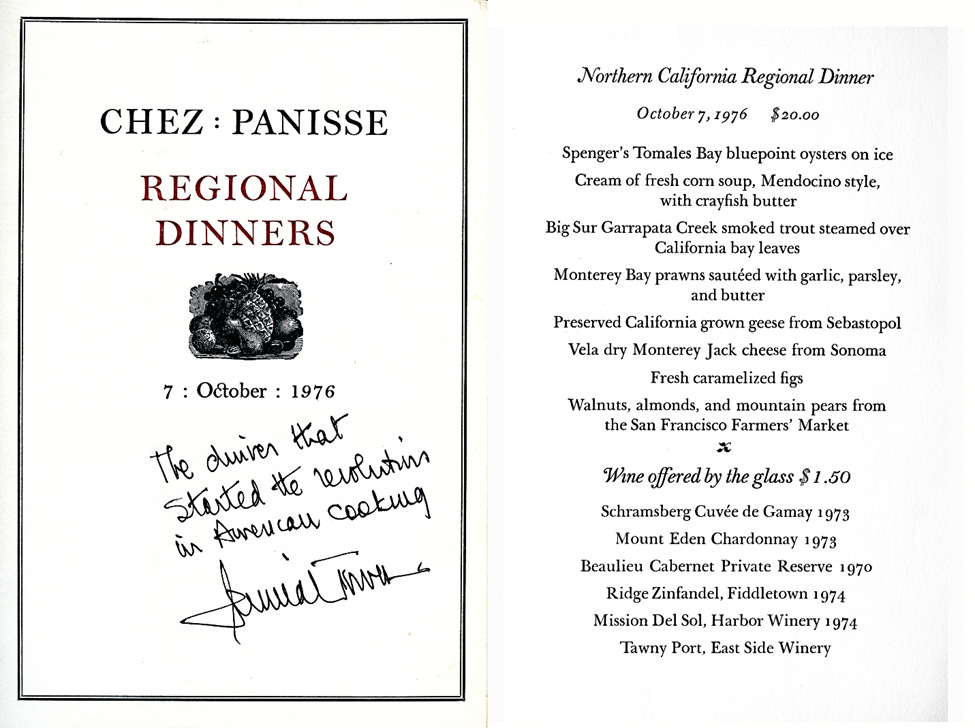

What has now become standard “locavore” and “farm to table” philosophy of cooking was started at this restaurant. Given such a highly publicized boost by Chez Panisse in 1973 and then with “California Cuisine,” most do not know that the first time menu phrases like “Our field greens are selected each morning and will vary daily,” as well as, under “Vegetables & Potatoes,” the comment that “Seasonal gatherings may be viewed in their baskets,” were first seen at The Four Seasons. There had been a “California Banquet” given in San Francisco in 1896, “the object of which was to prove the possibility of making up an extensive menu from the products of the state,” which I showed to Jim as my inspiration for the “Californian Regional Dinner” that I did in 1976.

His smiling comment to both California events was:

“Well, we did it first!”

When Jim Beard died he was testimony that if you stay vitally interested in life, you can still reach eighty-one despite what you eat.

Staying alive all those years was not greatest achievement. It was his helping others while helping himself. Beard jump started many a young chef’s career in the United States.

In 1974 Jim was visiting San Francisco, and he had just written in his widely-syndicated column that if he had to choose four restaurants in the United States to revisit, they would be New York’s The Four Seasons and Coach House, Tony’s in Houston, and the then unknown Berkeley’s Chez Panisse. To thank him, I invited him to dinner at the home of a friend.

I was very nervous to be cooking for him, let alone at home, with no backup staff or professional equipment. Up to the morning of the day of the dinner, I had no idea what to serve. I wandered around Chinatown in San Francisco, looking for inspiration. I saw several deep-sea urchins, each the size of a large grapefruit. I knew I must have them, whatever their preparation or place in the meal. When I faced them in the kitchen that afternoon, from somewhere a memory came of a recipe for sea urchin sauce that referred to using the sauce as the basis for a soufflé.

“Right,” I thought aloud. “Soufflés they will be.”

It was too late to buy individual soufflé dishes, so the shells just had to do. As I opened the oven door, my heart held by cold hands, I saw that the scheme had worked. The spines were intact, a wonderful ocean smell began to waft into the kitchen, and best of all, the soufflé mixture had risen above the crater like openings in the shells, puffy pink-beige, and beautiful. I rushed them to the table. Jim tried a spoonful. No word was said. He looked up slowly, aware of the theatrical effect, rolled his eyes slowly, and said:

“My God, that is the best thing I have ever tasted.”

Not true, but Beard was perfect at public relations, and it was the start of a long friendship.

Photo courtesy of Stock Food

Sea Urchin Soufflé in an Urchin

Serves 4

4 large whole sea urchins

2 ounces unsalted butter

2 tbs flour

1 cup fish stock

2 egg yolks

4 egg whites

salt and freshly ground white pepper

Using scissors, cut a hole around the inside perimeter of the underside of the sea urchin. Discard the cut shell and clean out the inside of the remaining shell, leaving only the pieces of orange-colored roe that sticks vertically to the shell.

Photo courtesy of Yummy Mummy

When the shell is perfectly clean, scoop the roe (gonads) into a bowl. When all the roe is out, clean the shells thoroughly and dry the inside surfaces. Purée the roe.

To make the soufflé base, melt 1 ounce of the butter in a saucepan. Add 1 tablespoon of the flour and cook over low heat for 5 minutes, stirring all the time. Heat the fish stock, add to the butter-flour mixture, and whisk until smooth. Cook over low heat for 30 minutes, whisking every 5 minutes and skimming off any scum that rises to the surface. Let cool to room temperature.

Heat the oven to 400°F.

Add the salt, pepper, egg yolks and the puréed roe into the soufflé base. Mix well. Rub the insides of the shells with the remaining butter and dust with the remaining flour. Beat the egg whites until stiff. Fold them into the soufflé base and spoon into the shells. Cook until the soufflés have risen and are slightly browned on top, about 20 minutes. Serve immediately.

Before my restaurant Stars in San Francisco (19840 and after the sea urchin souffle evening, and Chez Panisse, I had not resisted the insane temptation to move to Big Sur to revive to food operations at the failing and almost defunct Ventana Inn.

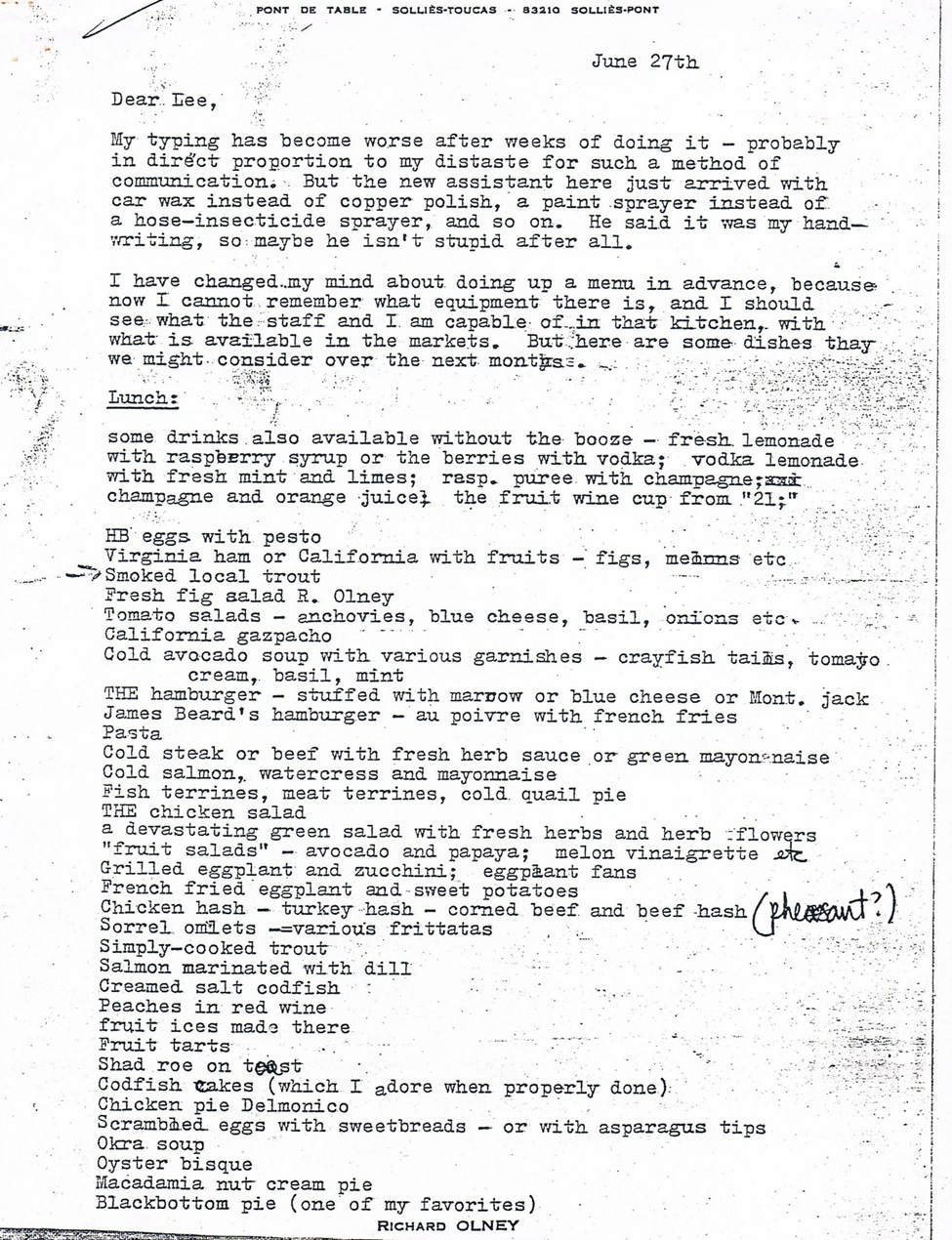

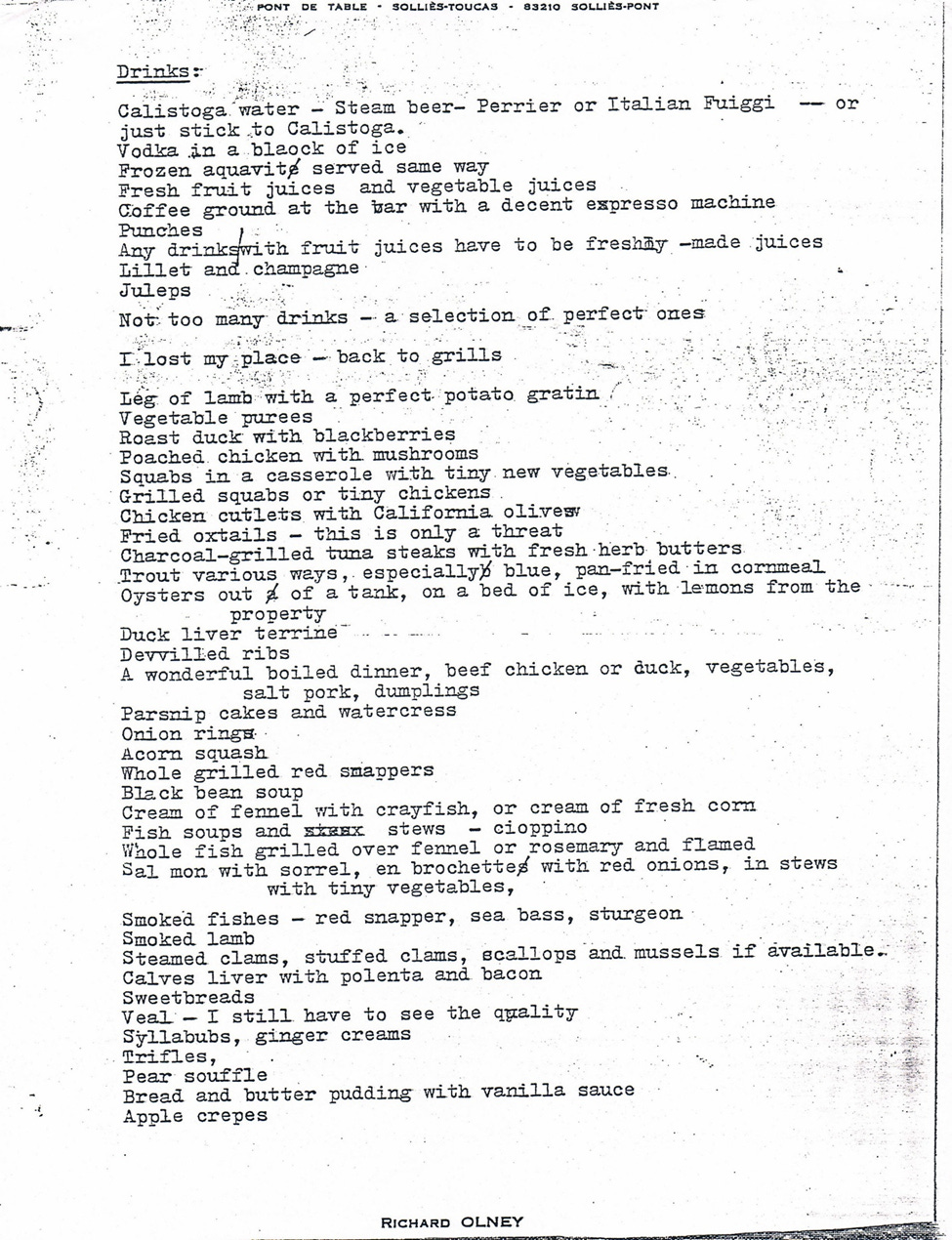

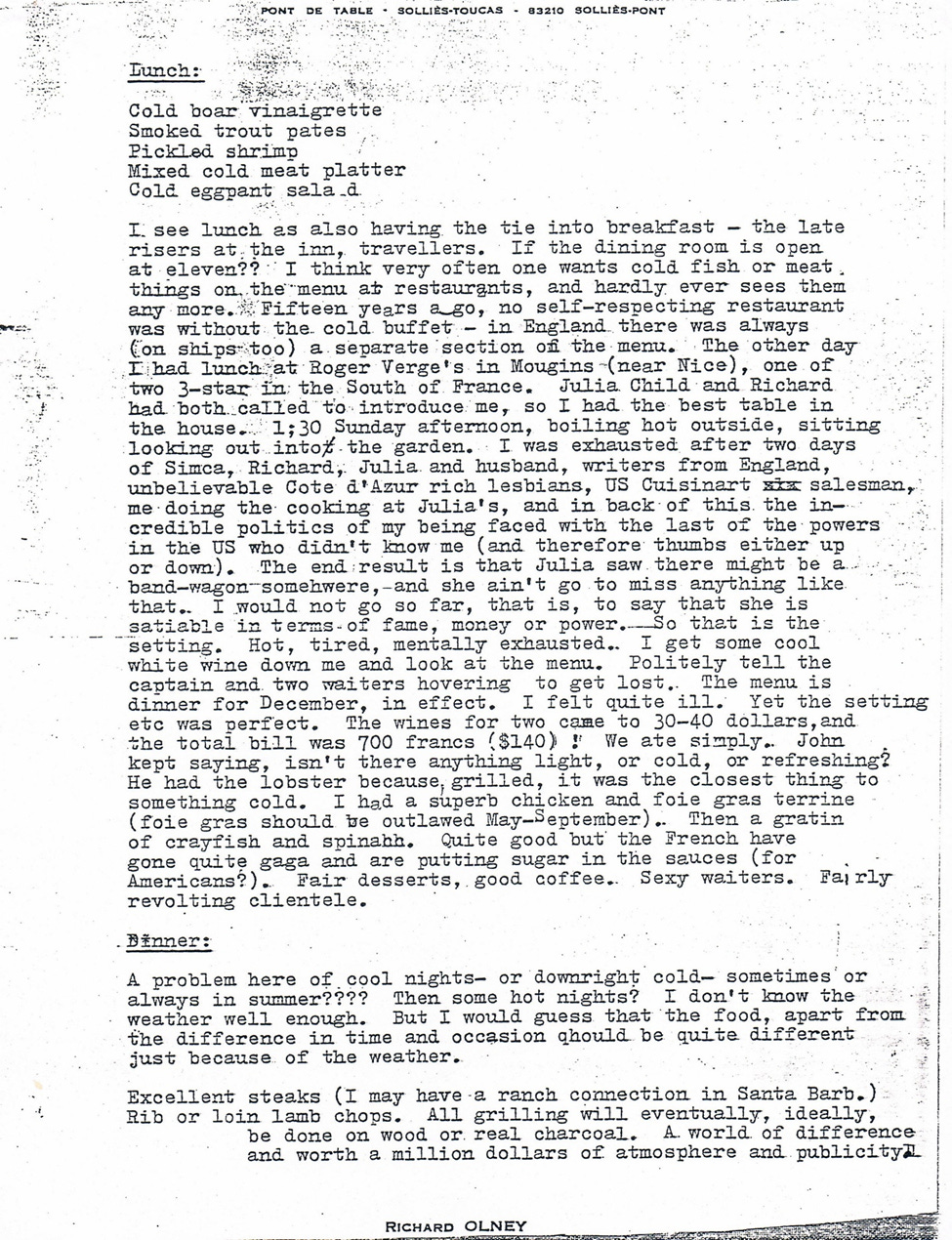

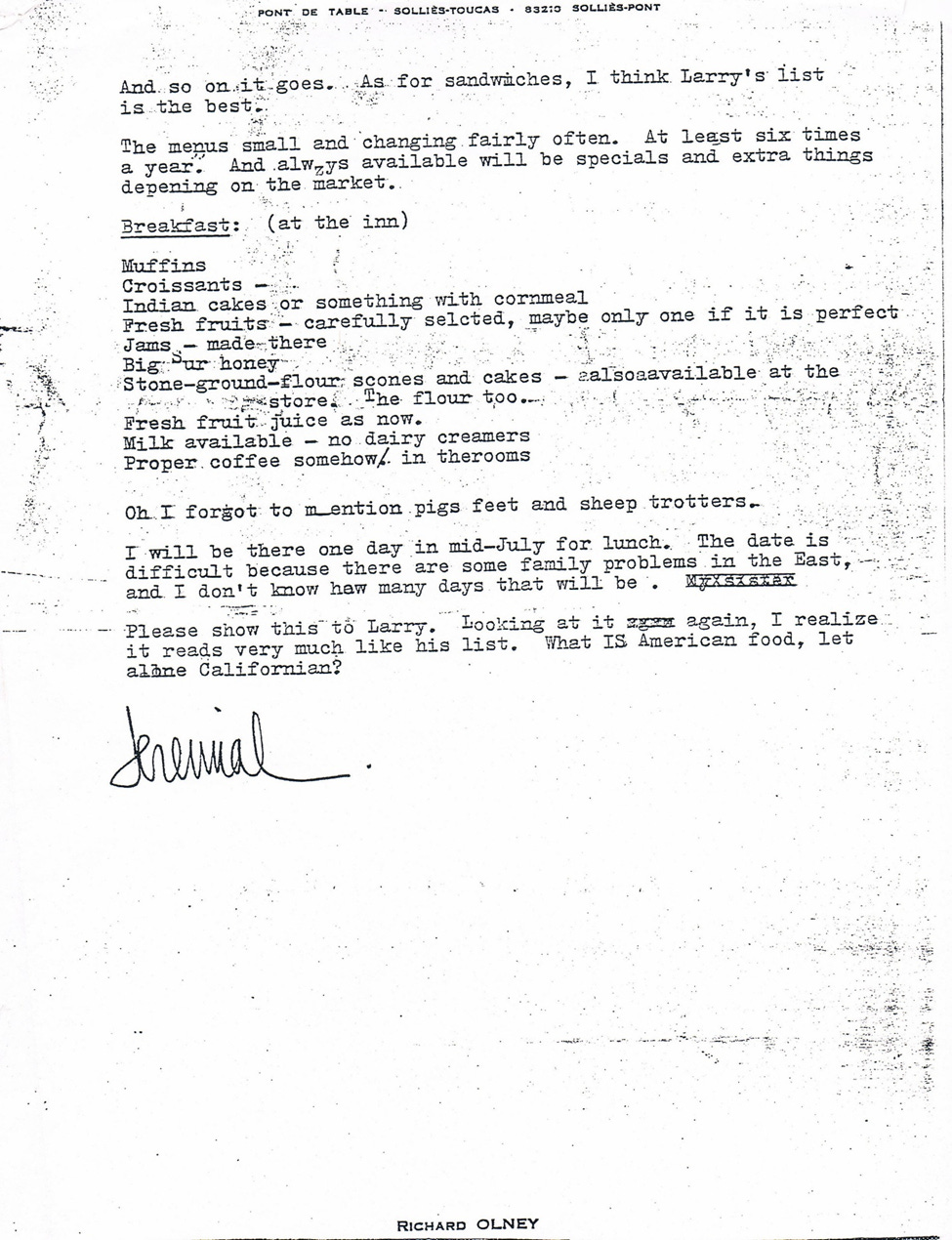

I moved into the restored original Pfeiffer homestead and started to rewrite the menus I had sent from the South of France and London while working with Richard Olney on Time Life’s and his masterpiece series called The Good Cook.

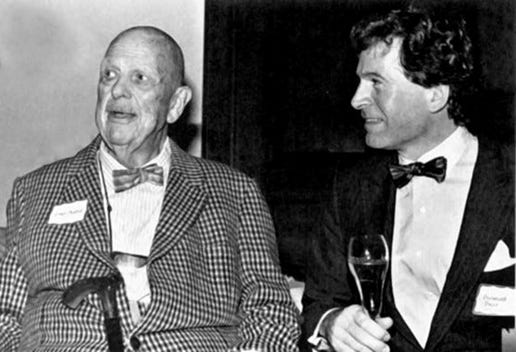

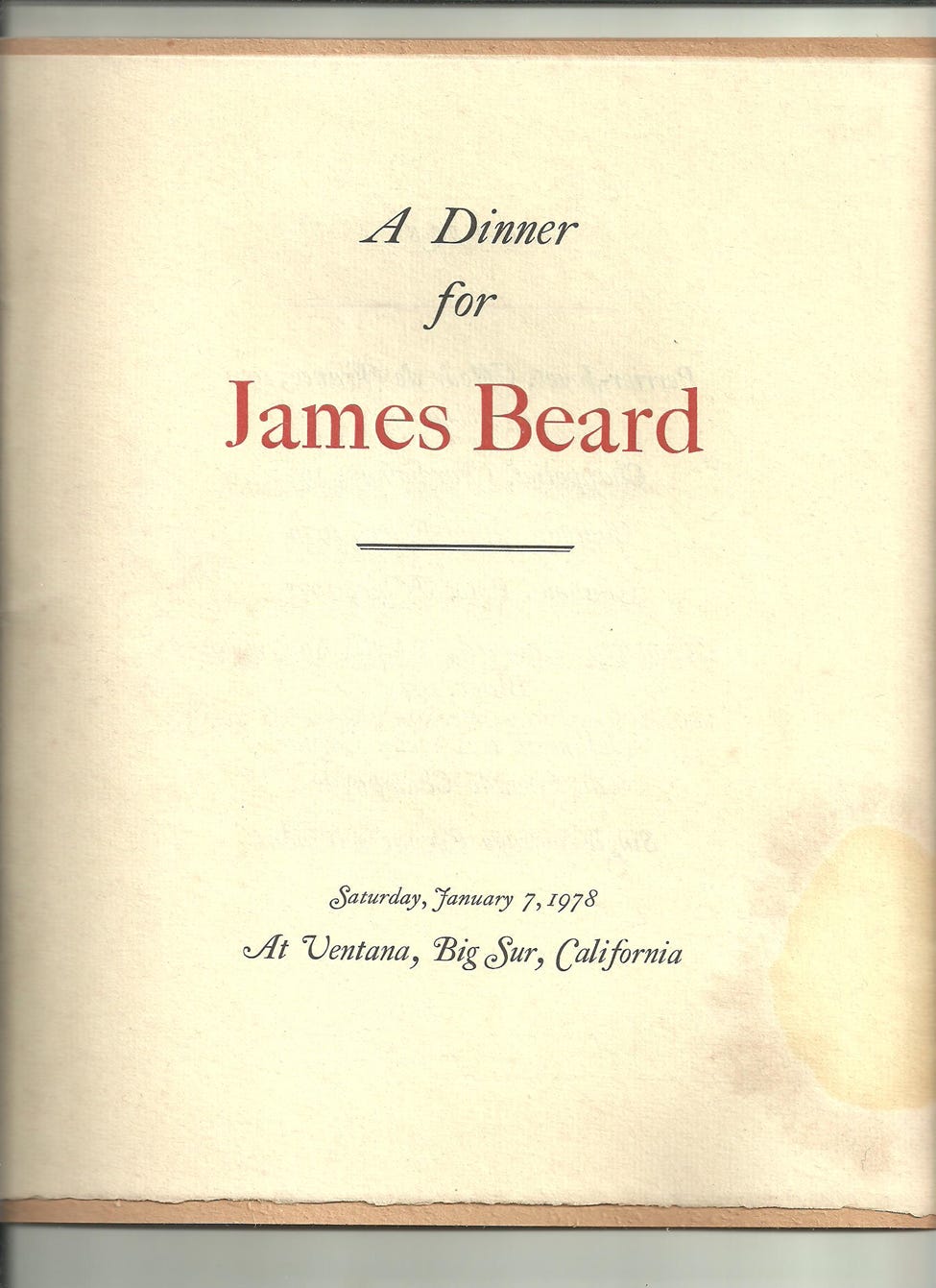

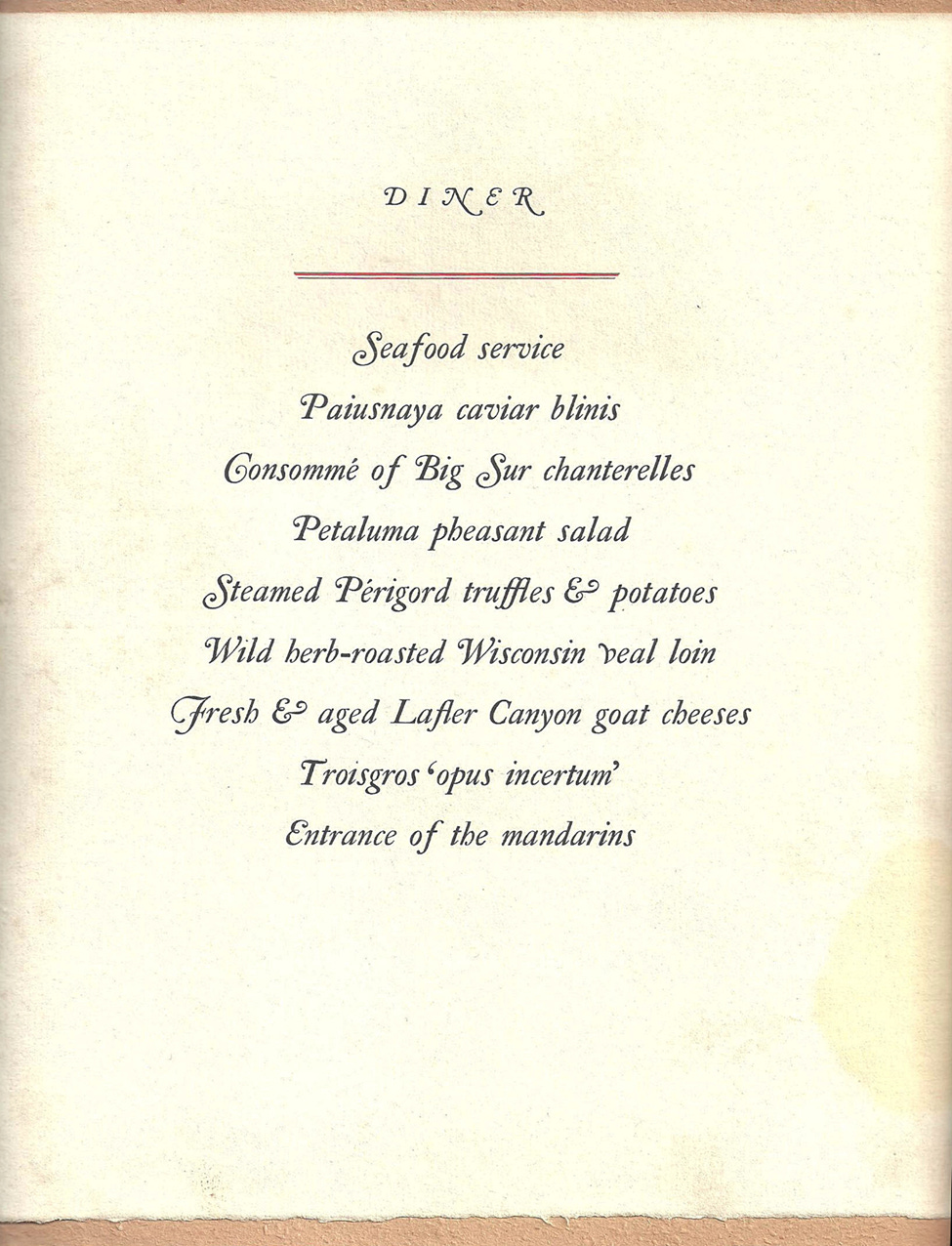

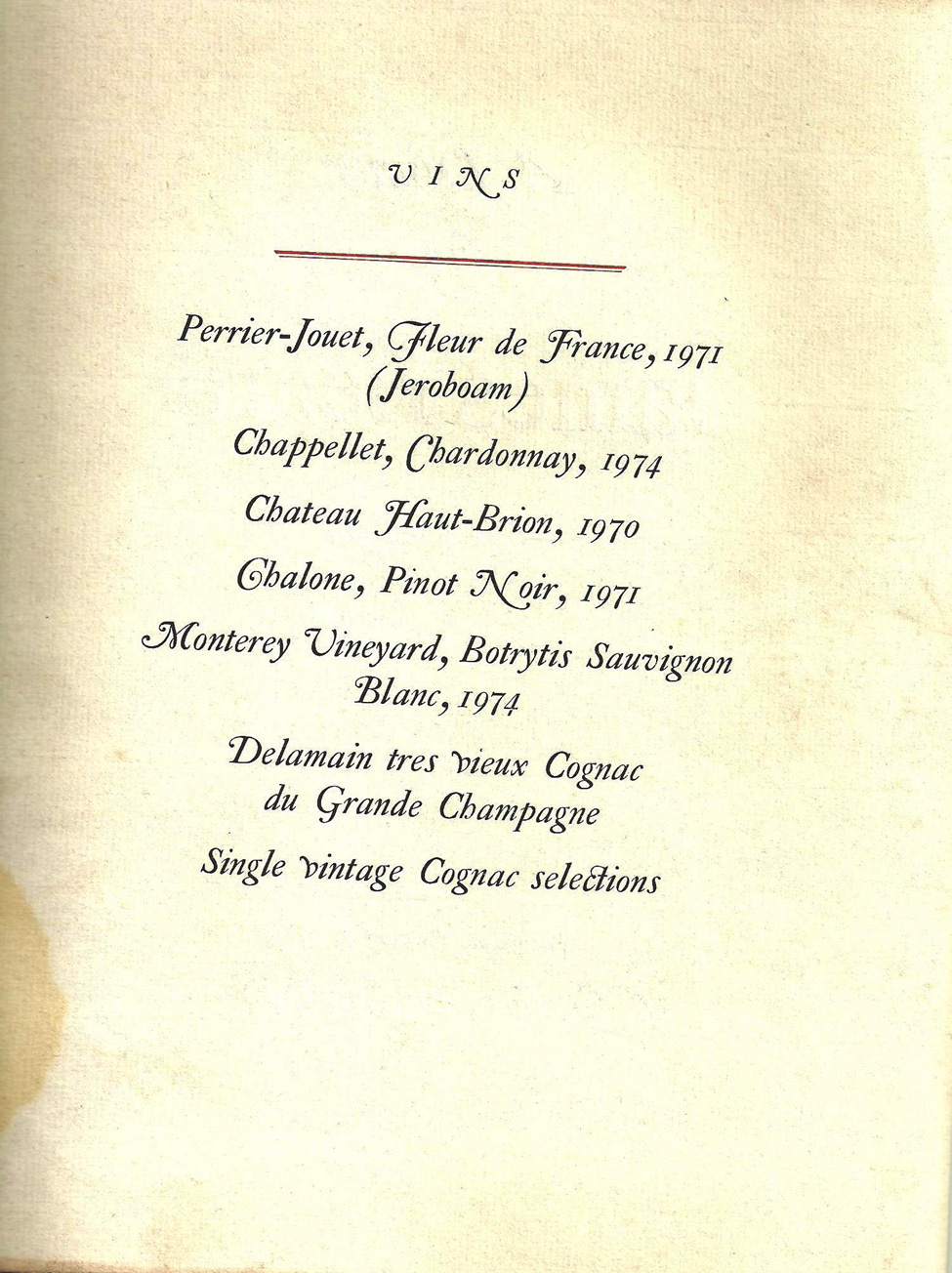

And who better than Jim to toot Ventana’s horn! I invited him and his California friends to a dinner.

I invited Alice Waters, Cecilia Chiang, Darrrel Corti, Marion Cunningham and a few more who would spread the word.

Lafler Canyon and its goat cheeses was 2 miles down the road.

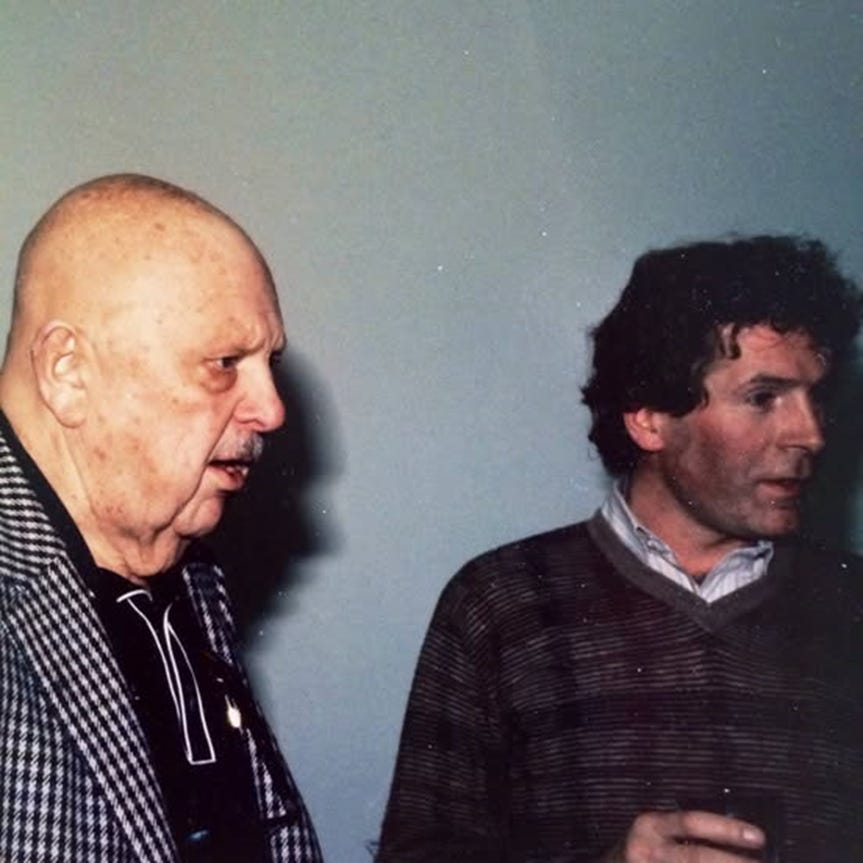

And here is a photo with Jim and Alice when it was all over and everyone very happy.

The next day at lunch at Emile Norman’s rach high up over Big Sur, I showed them some dishes from its new menu.

American Menu for Ventana Inn, 1978

Virginia ham with California fruits

Petaluma Chicken and Texas wild pheasant hash

Paso Robles peaches in its red wine

Monterey Wild boar, walnut vinaigrette

Parsnip cakes with Big Sur watercress salad

Roast Sonoma duck with Big Sur blackberries and green walnuts

Braised Pigs’ feet or sheep trotters on johnnycakes (instead of tortillas)

Turtle Cay bananas in rum with mango ice cream

Black bottom pie

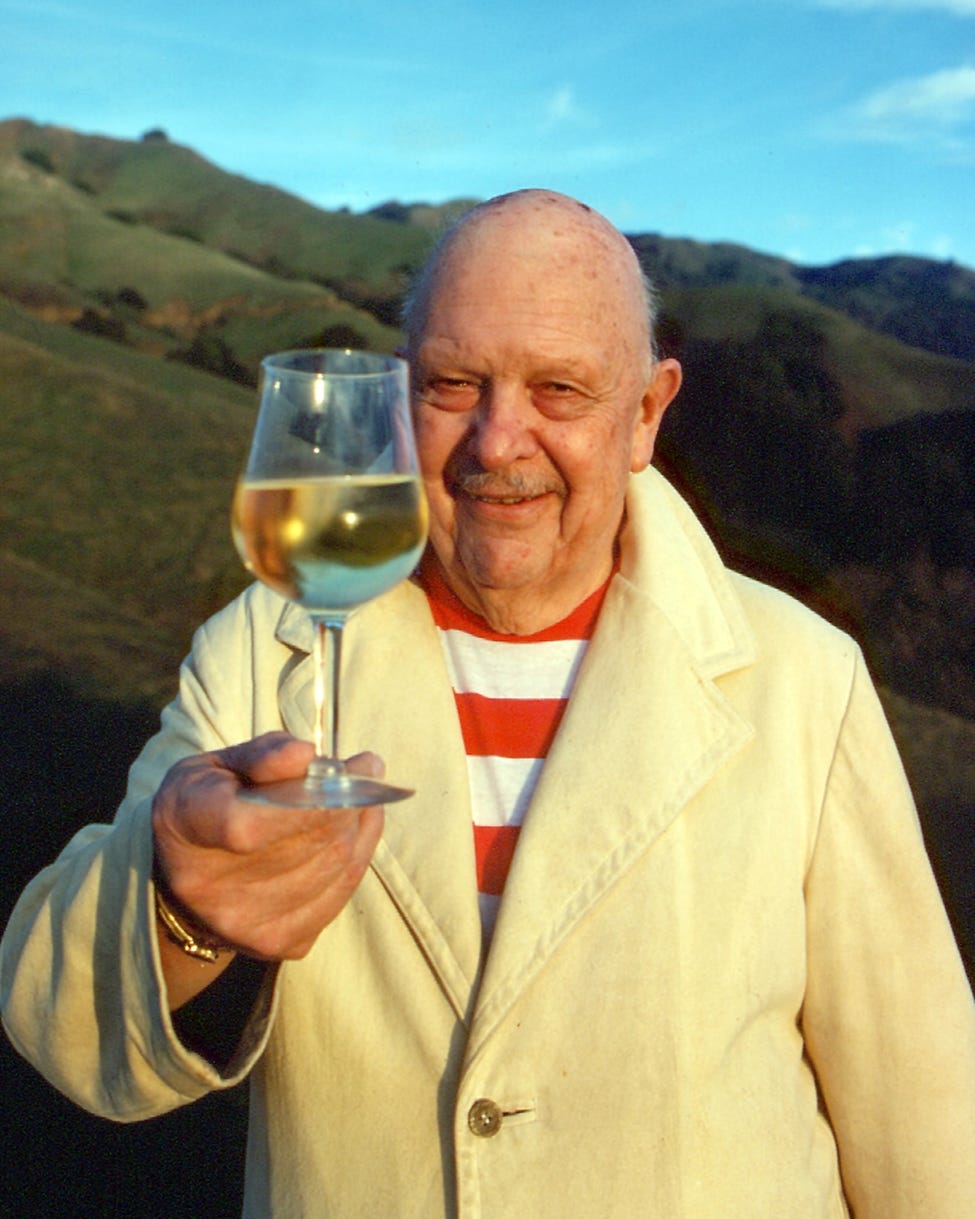

And then had a picnic in front of those Big Sur hills and took that photo of Jim holding a glass of wine.

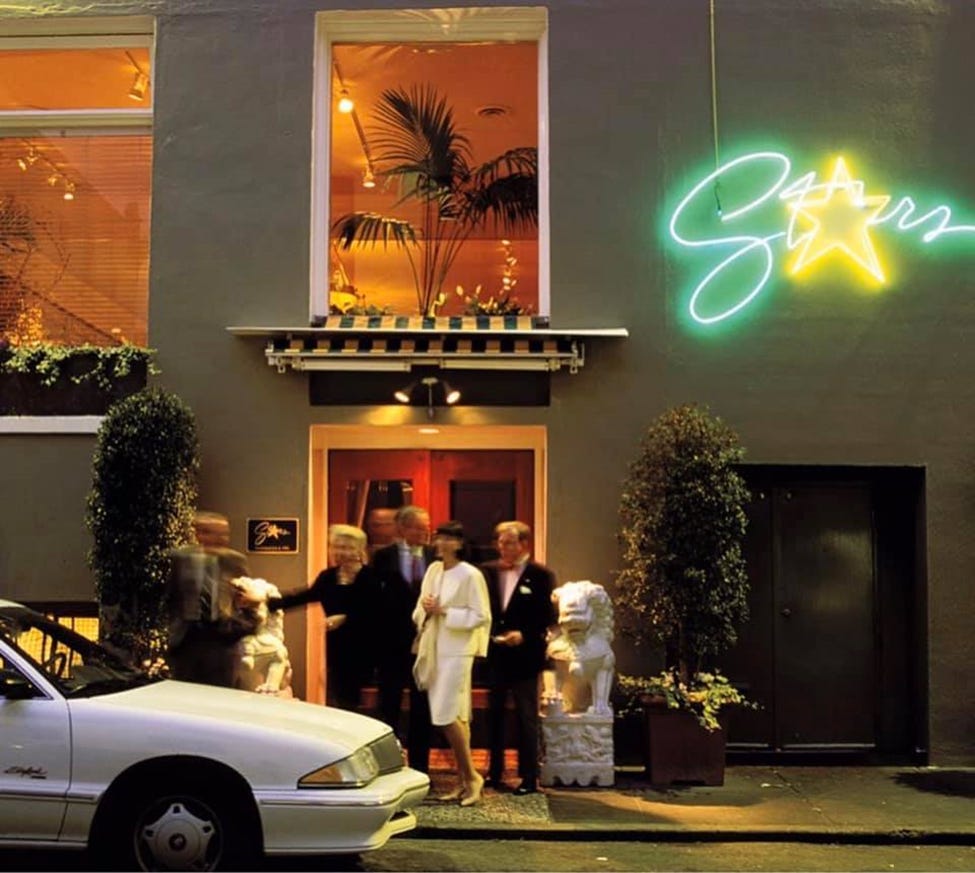

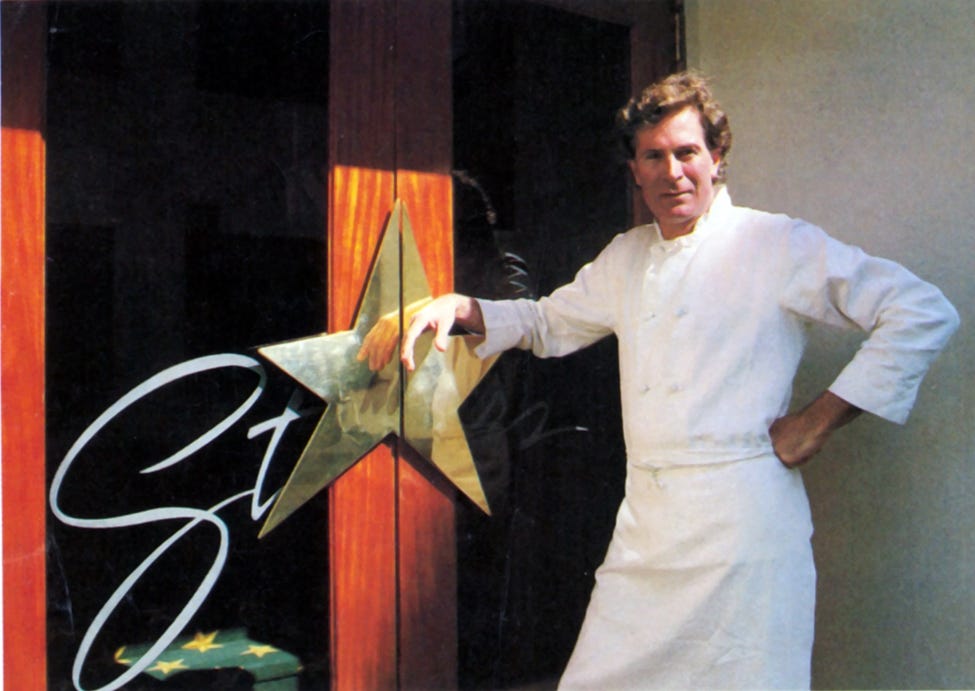

Stars San Francisco

One of my favorite memories of Jim is of his visit to the desolate and raw defunct-restaurant space that was to become my Stars. I saw only its glorious (I hoped) future.

That look of horror was in 1983.

All he saw was the filth, the rats avoiding his shoes, and the broken pipes spewing geysers of water across the old kitchen.

Then where was my restaurant Stars in San Francisco which open on July 4th 1984after a year of construction and permits.

The old kithen hood.

And the new one.

And starting on the dining room.

With Bruce Hill cooking for the crew.

Finally looking like this.

Certainly, one of the first open kitchens so the public could see all the theater of cooking over 300 lunches and 450 dinners.

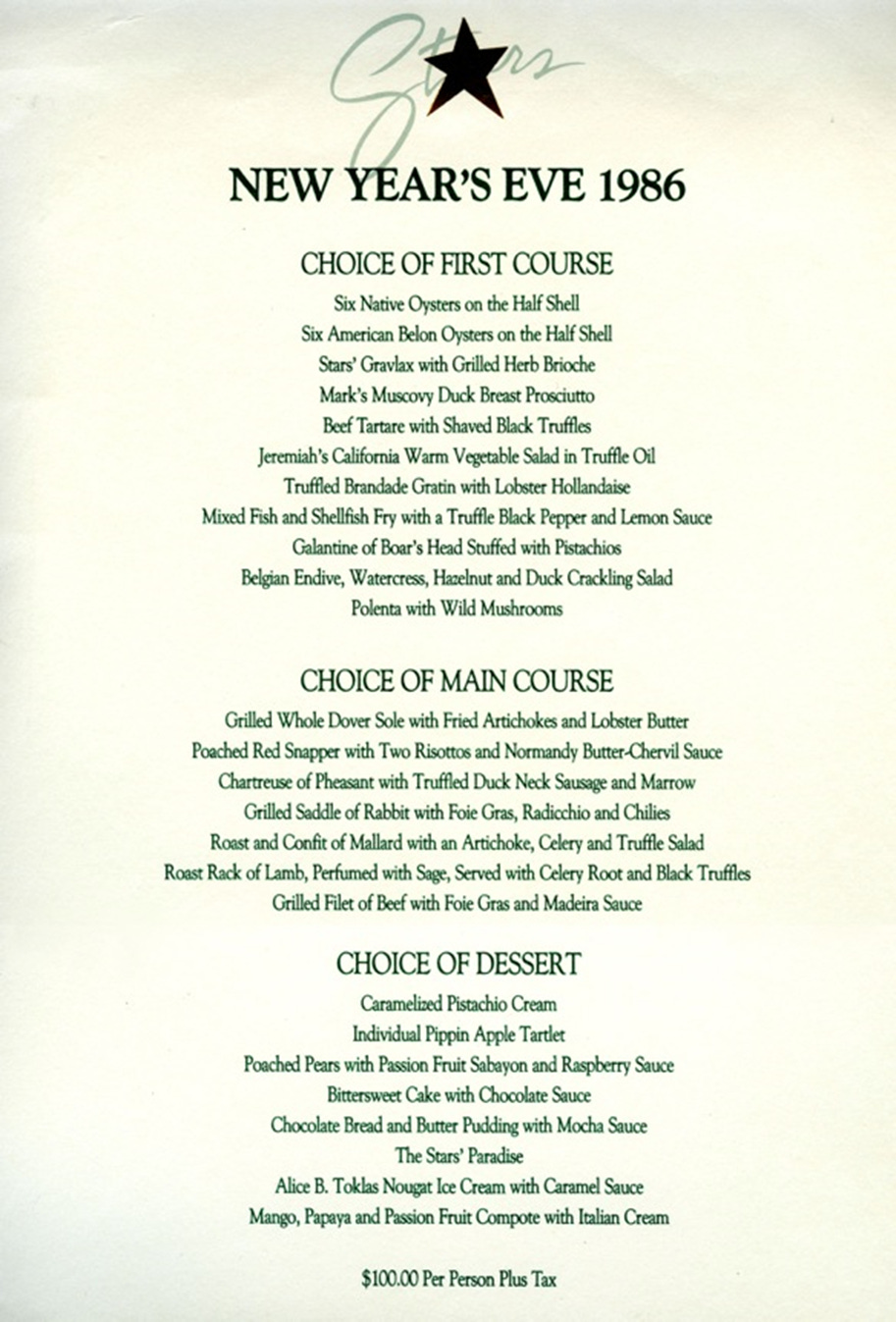

Serving this food.

And Stars’ 30-seat bar.

And a corner of the dining rooms.

And just as I had promoted Chez Panisse, Ventana, the Balboa Cafe, and The Santa Fe Bar & Grill

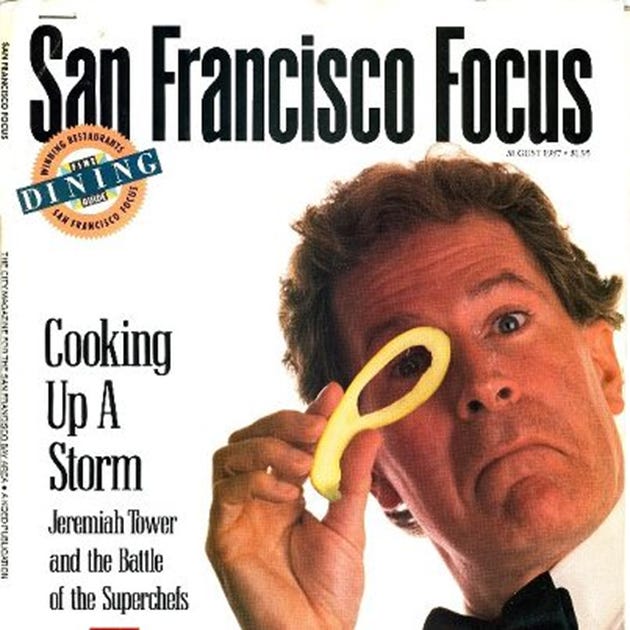

I now concentrated on Stars and showing it off with the power of celebrities.

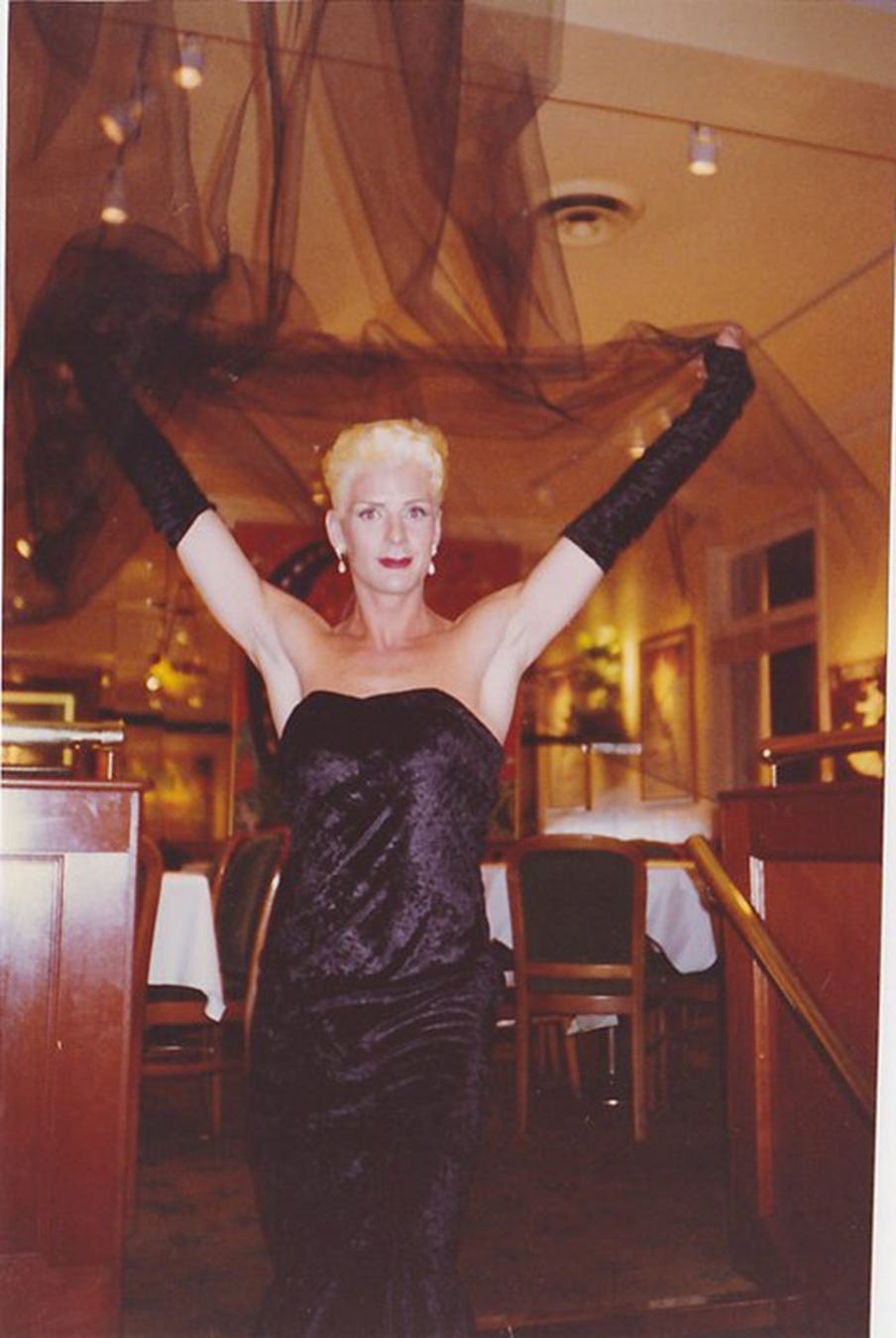

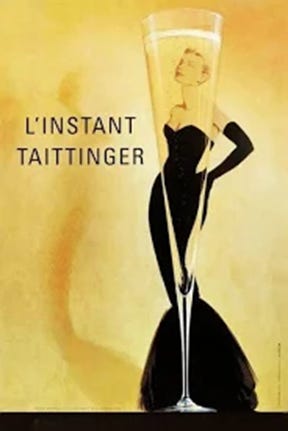

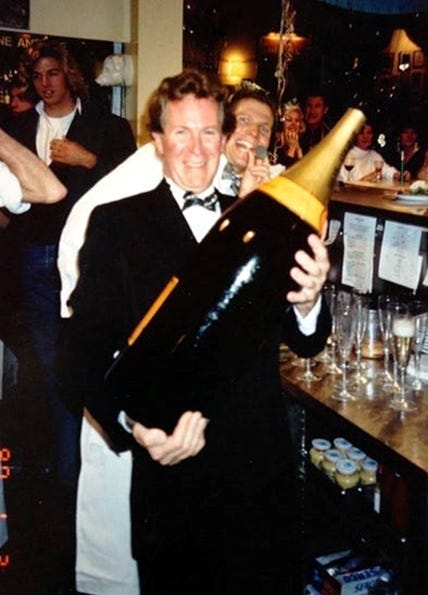

Let alone Jim’s favorite of the Halloween night at Stars. With a server dressed as one of the posters.

This one Taitinger hanging on one of the dining room walls.

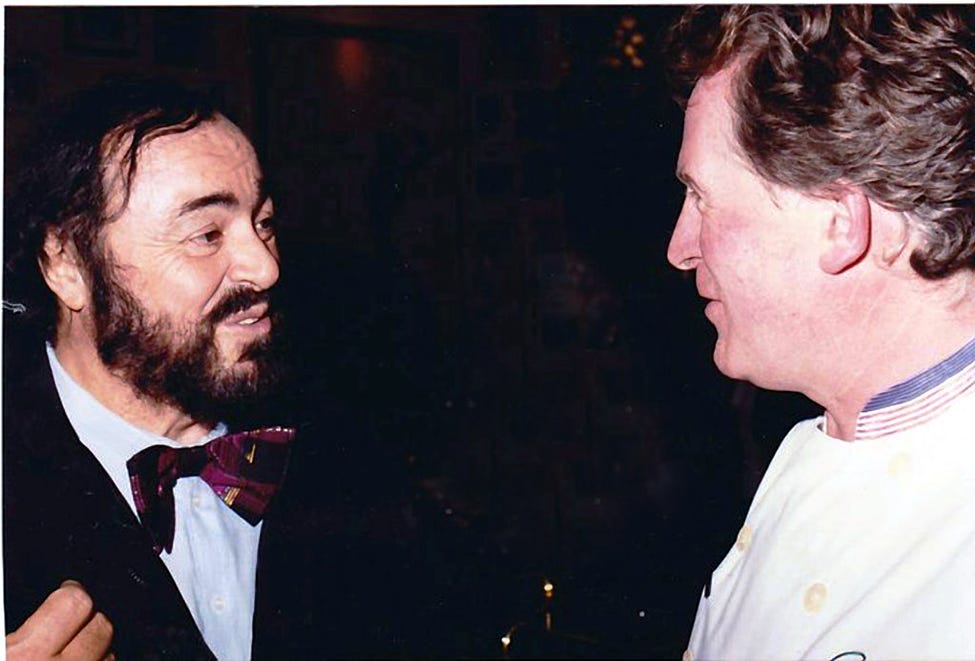

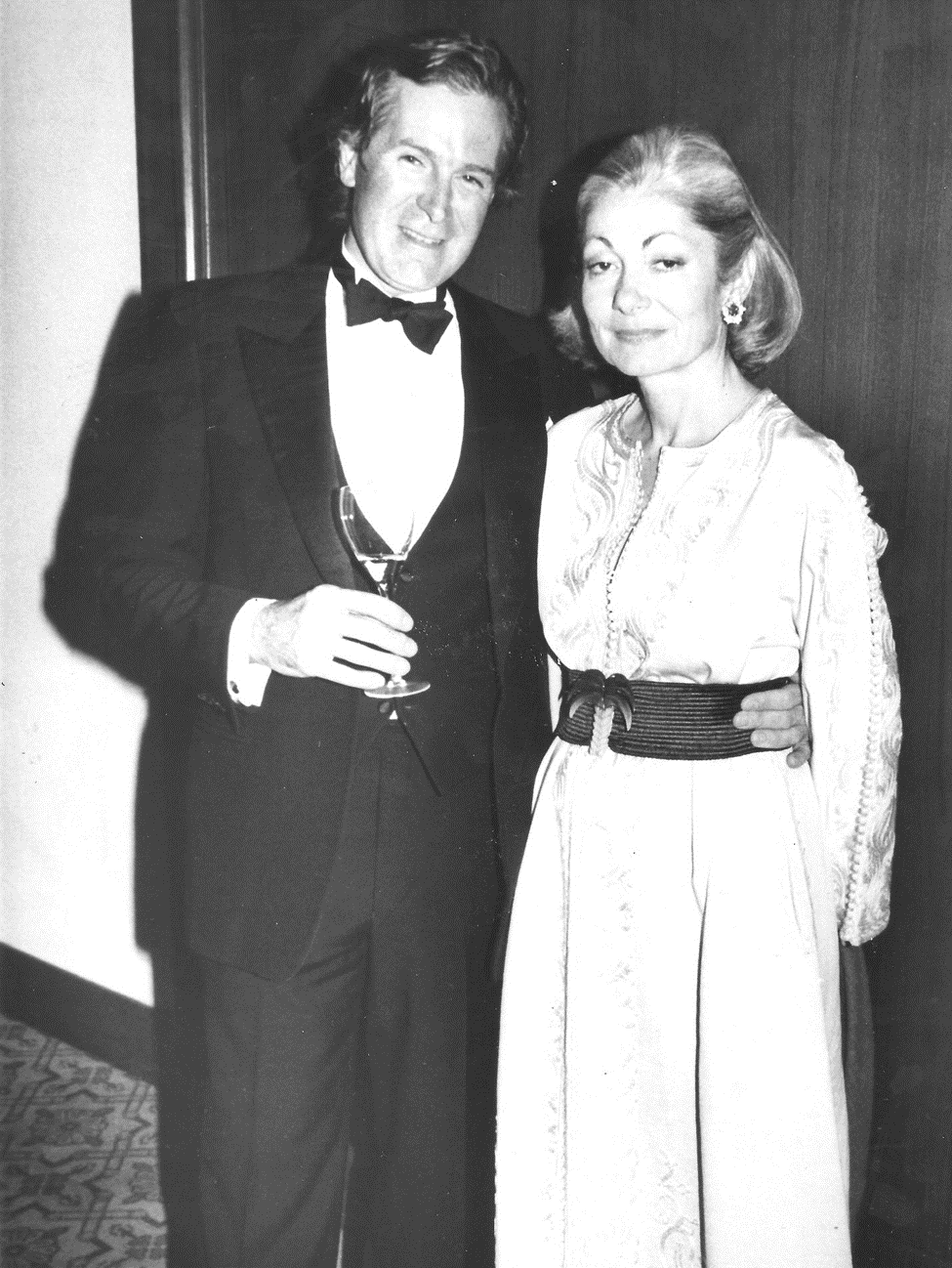

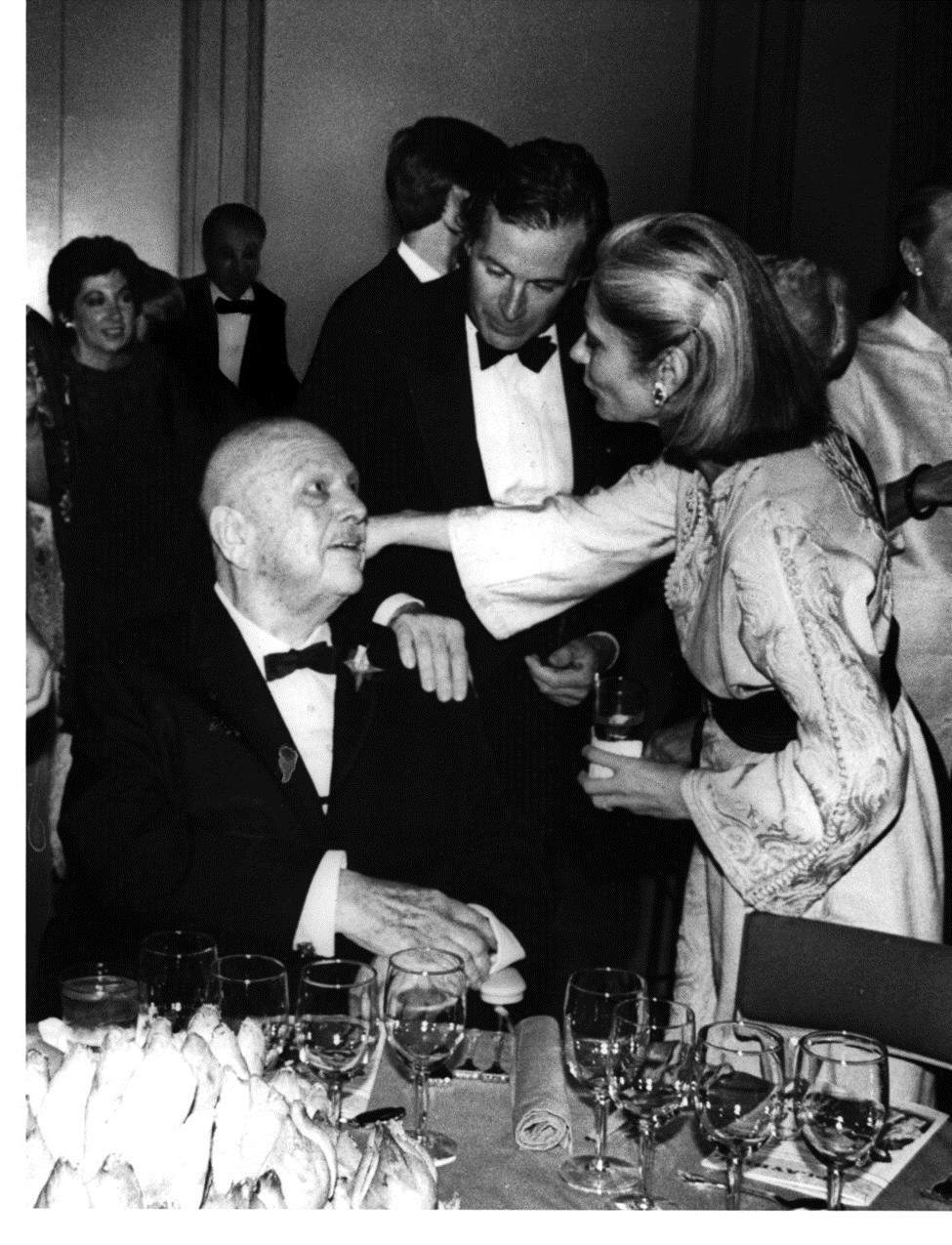

Jim and Stars’ greatest patroness, Denise Hale for whom he used to work

Buy some fresh jumbo lump crab meat, and gorge!

Sorry it was undercooked!