When thinking these days of the present, I wonder about the past and if it was as interesting as now. My grandfather would love to have his pal Herbert Hoover back, and for my father Thomas Jefferson would be just fine.

These days I am more certain than ever that there is no unified opinion of what from the past should be reclaimed.

So, I will stick to food. And cooking.

Throughout culinary history, my favorite cookery books are those that are based in the regional cooking of families, simple or grand, and which celebrated simplicity and directness.

In our urban societies, with the wellspring of inspiration no longer the family hearth, what is left is the cooking of restaurant chefs, chef writers, and the culinary press. The danger is that, as we see now on all fronts, the line of follow the leader forms such a small circle that everyone in the line has only a view of the back of the person in front. So perhaps it is time, again, to go back to moments of very clear vision in our culinary history to see what the future holds the next time someone steps out of line.

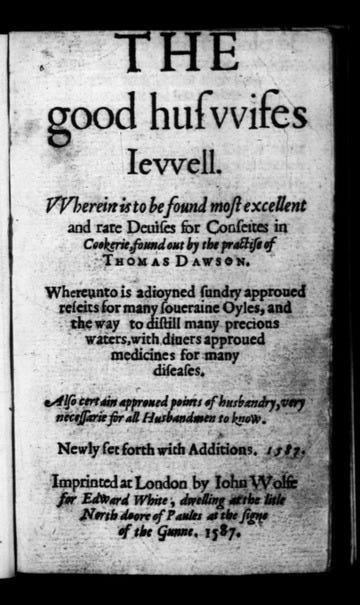

I have chosen, as food for thought, Thomas Dawson’s The Good Huswifes Jewell, published in London in 1596 and 1597 for Edward White, “dwelling at the little North doore of St Paules at the signe of the Gun.”

And no, I am not going to go off on a list of bizarre dishes or talk about myths like how spices were used to cover up rotting ingredients. Or bring up a lot of words like “muggings,” or wallow in archaic spellings, or relish the fascinating quaintness of the “husbandry” parts of any cookbook of the times (“an oyle to stretch sinews that be shrunk,” or which direction of the wind to back a ewe up against to get her in the mood).

I skipped books like Ancient Cookery from 1381, because how could I tell if the text held simple and direct material or not? I mean, it’s those “cranys, herons, and partrigchis” again, all of which “fshul ben yparboyld” first and then “etyn with gyngynyr.” And did I pass on the famous and beloved first English cookbook, The Forme of Cury, compiled by the master cooks of Richard II of “Englond.” But with spelling and punctuation like that for England, it’s all too much work, even if Forme has an elegant confidence not unlike Escoffier.

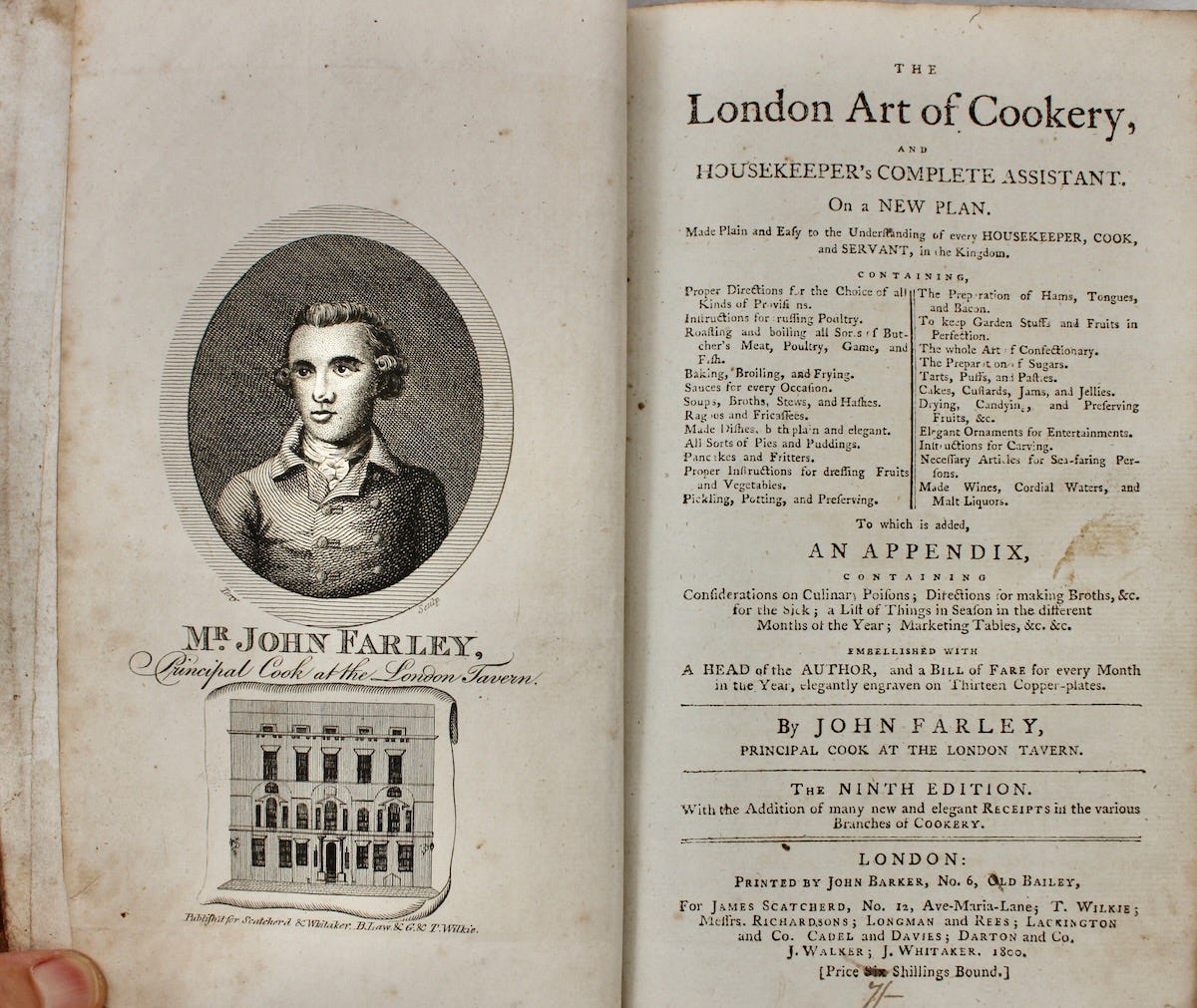

But I will stop for a moment in 1792, with John Farley’s The London Art of Cookery. Farley was the “principle cook at the London Tavern” and such a location, accounts perhaps for the democratically approached and concisely worded book.

This is simple food, and the recipes are beautifully written. “Slit your chickens down the back, season them with pepper and salt, and lay them on the gridiron, over a clear fire. Let the inside continue next the fire till it be nearly half done. Then turn them, taking care that the fleshy sides do not burn, and let them broil ‘til they are of a fine brown. Have good gravy sauce, with some mushrooms, and garnish them with lemon and the broiled liver, and the gizzards cut and broiled with pepper and salt; or you may use any other sauce you fancy.”

Sounds like Elizabeth David 150 years later!

Those who would prefer I glorify roasted peacocks served forth in silver leaf will be disappointed since there are none in the books that I am reading.

In Farley there is a whole boned turkey, or baked artichoke bottoms serving as a nest for a sparrow, the sauce preserved lemons and butter, but mostly the book has recipes like duck with turnips, onion soup, or how to make a rich broth that has no fat in it.

For a strawberry tart we are asked to soak them in a little claret wine, and then to heat and reduce the berries briefly with a few drops of fresh rosewater added. Then a little sugar and ginger is mixed in, the mixture spread in a baked tart shell, the edges of the pastry are painted with butter, the strawberry mix topped with some crushed biscuit (think macaroons) crumbs and the tart is then very briefly baked.

That should stir the juices of thought.

Pears to be served with boiled meats are poached in beef broth, put in a baking dish with mace and saffron beaten and heated with egg yolks into the rich broth to thicken it, and gently warmed for serving.

Onions for soup or as a garnish for chicken are cooked in almond water (blanched almonds ground up and soaked in water then strained out) then thickened again with egg yolks and flavored with a bit of clove and bay leaf.

The dish of poached quail reminds of my mother’s hotpot soup of chicken with parsley root and leaf, carrot, basil, and lots of what tasted like lovage but was probably just fresh celery leaves. The 16th-century calls for a clear broth for the quail, flavored with parsley root and leaf, carrot, sweet herbs, ginger, nutmeg and pepper, and a little verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes).

Confident simplicity.

Let perfect ingredients do the walking and talking. Dawson’s recipe for fried chicken is a lesson in how little is on the plate when the recipe is perfectly orchestrated.

Poach a whole chicken in chicken-almond broth and cook it three-quarters of the way. Let it cool in the broth, then take it out and cut it in serving pieces. Then put the pieces in a frying pan with lots of very best quality butter and “stew” (over low heat) the pieces in the butter until finished cooking, but never browned. Then remove all the butter. Take a cup of the poaching broth and beat it with two egg yolks, nutmeg, ginger, and pepper, and pour it over the chicken in the pan. Warm it all through until the sauce is just thickened.

Serve it the way it is, or scatter some lemons cured in sugar and salt.

Amen.

Then let’s look at 20th-century SIMPLE EVERY-DAY COOKING.

No stargazing will occur here.

I have chosen the books that the likes of Elizabeth David, Jane Grigson, Richard Olney, and James Beard thought the best. It was when rereading these old select cookbooks for these columns, I realized what they all have in common: an ease of reading that comes from the directness, simplicity, and lack of pretension.

But looking at America for a minute, at a family manuscript gathered between 1749 and 1799, called Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery it is obvious they were then looking at the same English books that I have been.

As long as we are jumping a hundred years at a time, we might as well land in London again, for some Every-Day Cookery for Families of Moderate Income, a good idea now that moderation has been forced upon us by ingredient inflation. This little book directs itself at the daily perplexity of “What to Cook, and How to Cook It.” It’s all about good food at small cost, and perfect, seasonal, ingredients.

Remembering that lobsters used to be cheap, the lobster sauce for poached turbot makes my mouth water.

“Pound the coral of the lobster and pour upon it two spoonfuls of gravy (rich beef jus), strain it into some melted butter, then put in the meat of the lobster, give it all one boil only, and add the squeeze of a lemon; you may, if you please, add two anchovies pounded.”

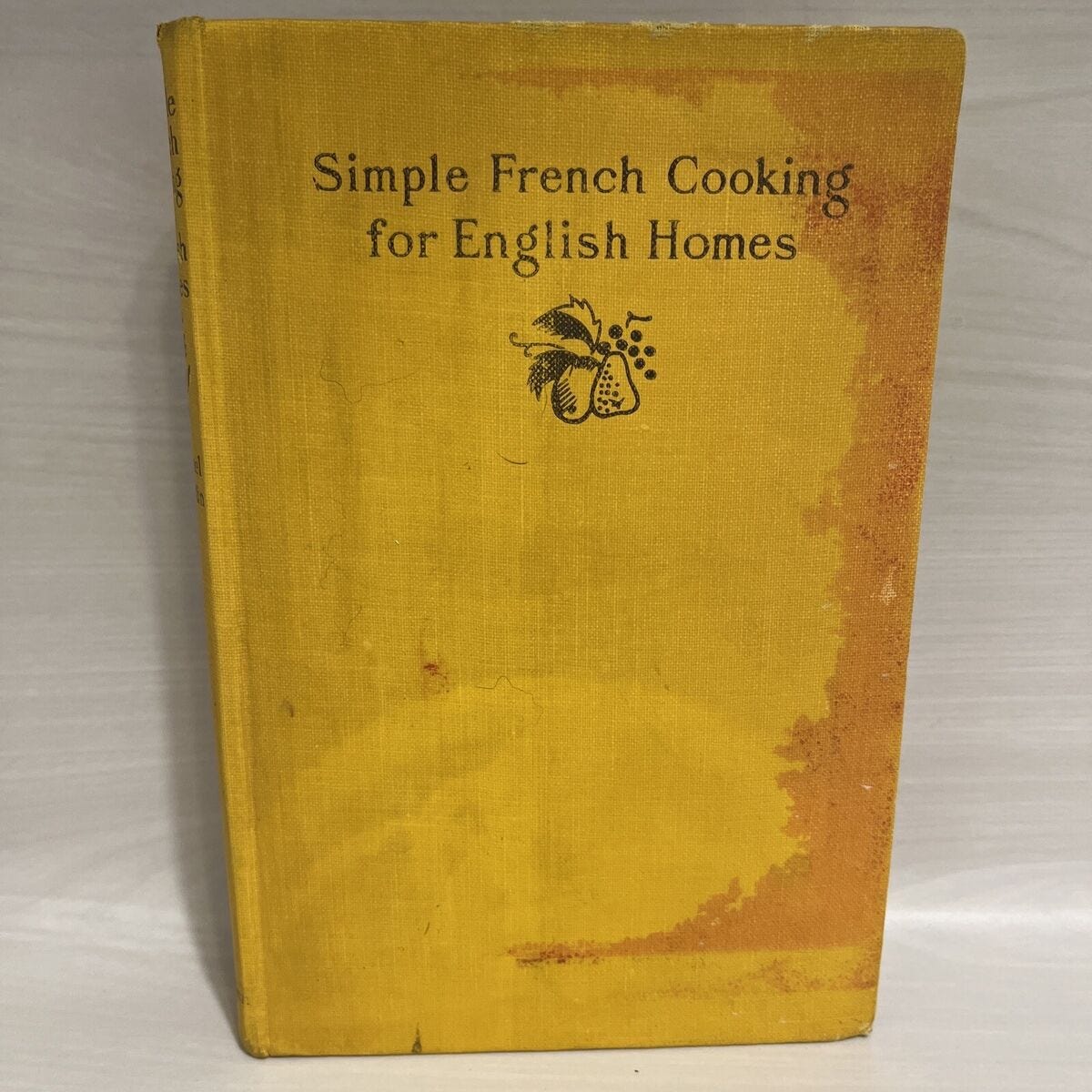

It is particularly the “if you may,” and “if you fancy” in the recipes that I find charmingly and newly democratic, the culmination of which appears thirty years later in the simple approach of X. Marcel Boulestin, the French answer to all of the early 20th century English housewives’ complaints.

The preface to Simple French Cooking for English Homes (1923) is where Boulestin states case that good cooking does not have to be “complicated, rich and expensive.” And is not the ubiquitous hotel and restaurant food where there is, he says, always a white sauce for the fish and a brown one for the meat. At home don’t ruin the special taste of the juices obtained from braising or roasting by adding “classical stock” which gives to all sauces the “same deplorable taste of soup.”

Be confident that a soup made from boiling leeks and potatoes in salted water until tender, then adding ripe tomatoes and cooking another five minutes, sieving it, and enriching the soup with farm quality butter, is enough impact for anyone. Then, for the rest, let imagination run its course.

A sorrel puree in which coddled eggs are buried before putting it under the broiler.

Poached eggs on a bed of fresh white corn (truffled or not), a creamed puree of sorrel spooned over.

An omelette stuffed with fresh salsify flowers.

A whole chicken cooked in a casserole over a deep bed of potatoes, whole pink garlic cloves, fresh cepes, and artichokes.

Fresh peas cooked with lettuce and little white onions, finished with fresh mint butter.

Spaghetti and puree of foie gras cooked in layers au gratin.

A truffle wrapped in bacon, wrapped, cooked in the ashes of the fire, and served on a puree of onions.

You know, simple food, and only sometimes expensive.

Many thanks for reading “Jeremiah Tower’s Out of the Oven.”

Your choice of my personal archives of my career as a chef at Chez Panisse, Stars San Francisco as well in Hong Kong, France, Italy, Australia, and Hong Kong. Accounts of cooking all over the world, for the most modest to the most famous like James Beard and Julia Child.

For $5 a month or $50 a year, you will receive weekly publications that include photos, menus, recipes, and videos of me cooking. Forty years of past ones like, “Chicken with Julia Child”, a film with Anthony Bourdain, the Pebble Beach Food & Wine festivals, and future events like the 2025 F&W in Ojai.

Nice to hear your clear and sensible voice again, and good advice, as always. Thanks!