Here I am in the company of 125 “global chefs” at the Pebble Beach Food & Wine festival, where I am hosting, “California Costal.” All my partner chefs work in California and there are 24 of them. I make up the 25th (though not cooking here anymore).

In making the list of 125 some chefs may have been forgotten. Making me wonder what great chefs from the past, like Alexandre Dumaine, should we remember now for instruction and inspirations. You read about the heritage of Dumaine in this inspiring Gourmet article by my pal Naomi Barry. About the genius of finding the perfect ingredients. http://www.gourmet.com.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/magazine/1960s/1964/02/alexandredumaine.html

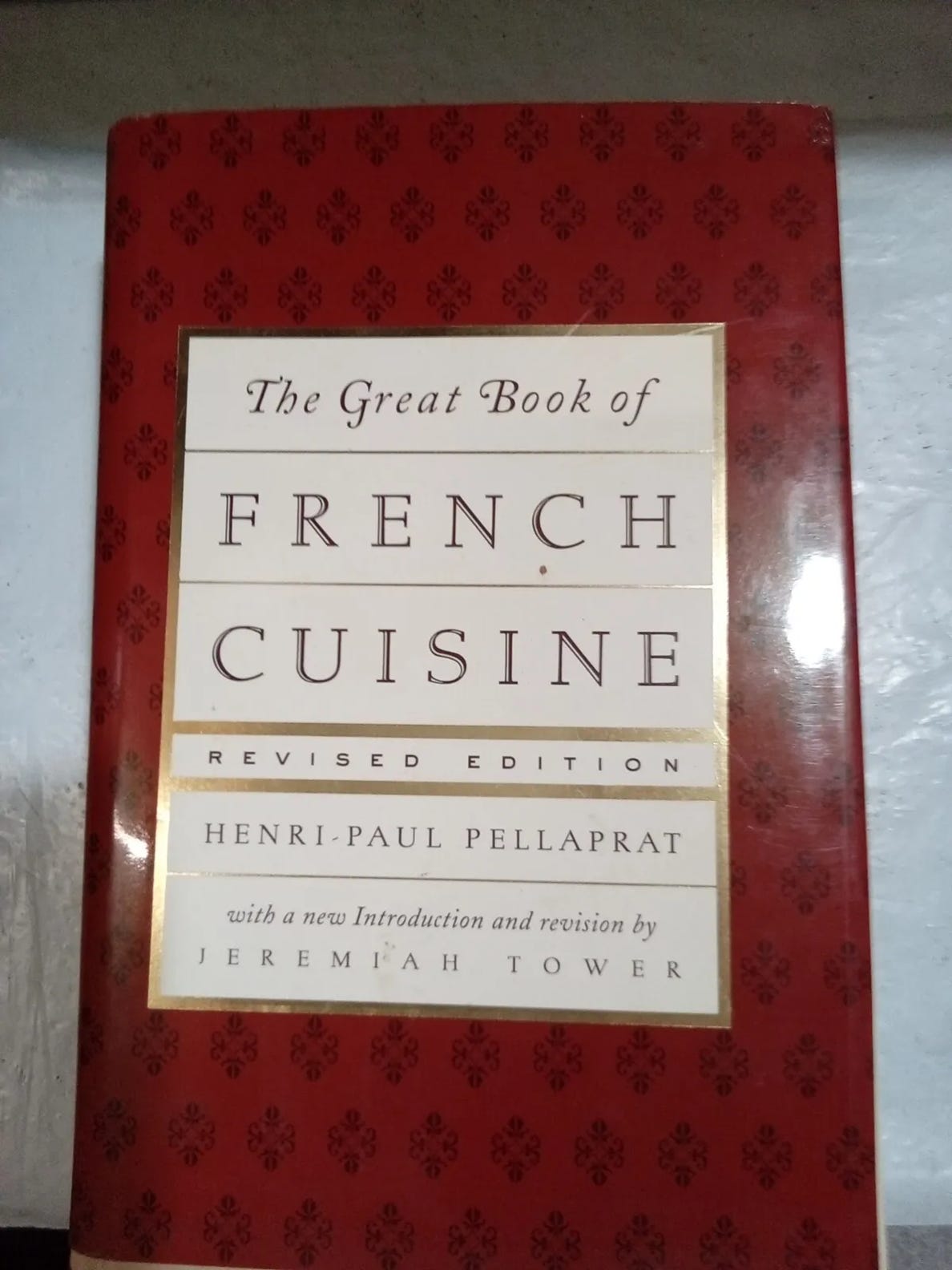

In the lobby on the way in to look at where the event would be, I saw a copy of this famous book where it talks a lot about what it means to be a chef. Reminding me that this “Great Book” helped me while head chef at Chez Panisse to become exactly that.